"Similar groups that display features of an ethnic group while being definable in social or religious terms were not a rarity in the Balkans. Such groups were for instance the Vallahades (Greek-speaking Muslims in Macedonia), the Dönmes (Muslims of Jewish origin in Thessaloniki), the Pomaks (Bulgarian Muslims), the Linovambaki and Laramans (cryptoChristians in Cyprus and Albania, respectively), and many others. There is also the remarkable case of the Karagüns ― from Turkish kara gün (“black day”), a population of Albanians in southwest Thessaly that distinguished itself through constantly suffering from malaria. (Rizos 1998)"

SOURCE

Reassessing ethnic identity in the pre-national BalkansRaymond Detrez (Ghent University, KU Leuven)

Abstract Ethnic communities have been investigated so far mainly by anthropologists and ethnologists. As the specific research tools they have developed are not applicable to communities that have disappeared a long time ago, historians have searched for evidence of ethnic consciousness mainly in political statements, while literary historians have focused on egodocuments. However, a critical study of these and other written sources reveals that in the Balkans prior to the nineteenth century ethnic allegiance occupied a far more modest place in the hierarchy of moral values than is usually assumed. People identified with a religious community in the first place, to a large extent neglecting or ignoring ethnic distinctions and feeling no compelling moral liabilities regarding the ethnic community they belonged to. Obviously, religion is not a component of ethnic consciousness, as is so often claimed. Ethnic identity transpires to be rather a local variant of a larger, essentially religious collective identity. This state of affairs seriously challenges the traditional assumption that national communities organically “continue” ethnic communities.

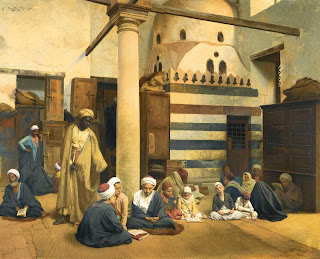

(Pictured) "Young Greeks at the Mosque" (Jean-Léon Gérôme, oil on canvas, 1865); this oil painting portrays Greek Muslim recruits into the Ottoman Janissary corps at prayer in a mosque.

See also: Greek Muslims

Mavi Boncuk |

The Vallahades (Greek: Βαλαχάδες) or Valaades (Βαλαάδες) were a Greek-speaking, Muslim population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They numbered about 17,000 in the early 20th century. They are a frequently referred-to community of late-Ottoman Empire converts to Islam, because, like the Cretan Muslims, and unlike most other communities of Greek Muslims, the Vallahades retained many aspects of their Greek culture and continued to speak Greek for both private and public purposes. Most other Greek converts to Islam from Macedonia, Thrace, and Epirus generally adopted the Turkish language and culture and thereby assimilated into mainstream Ottoman society.

The name Vallahades comes from the Turkish-language Islamic expression vallah ("by God!"). They were called so by the Greeks, as this was one of the few Turkish words that Vallahades knew. They were also called pejoratively "Mesimerides" (Μεσημέρηδες), because their imams, uneducated and not knowing much Turkish, announced mid-day prayer by shouting in Greek "Mesimeri" ("Noon"). Though some Western travellers speculated that Vallahades is connected to the ethnonym Vlach, this is improbable, as the Vallahades were always Greek-speaking with no detectable Vlach influences.

Ethnographic map of Macedonia (1892). Those defined as Greek Muslims are shown in yellow

The Vallahades were descendants of Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians from southwestern Greek Macedonia who probably converted to Islam gradually and in several stages between the 16th and 19th centuries.[6] The Vallahades themselves attributed their conversion to the activities of two Greek Janissary sergeants (Ottoman Turkish: çavuş) in the late 17th century who were originally recruited from the same part of southwestern Macedonia and then sent back to the area by the sultan to proselytize among the Greek Christians living there.

The Vallahades were resettled in western Asia Minor, in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca, Kırklareli, Şarköy, Urla or in villages like Honaz near Denizli.[17] Many Vallahades still continue to speak the Greek language, which they call Romeïka[ and have become completely assimilated into the Turkish Muslim mainstream as Turks.

![]() Villages of the Vallahades around Anaselitsa SOURCE

Villages of the Vallahades around Anaselitsa SOURCE

There were pockets of them scattered amongst the Greek population of south-west Macedonia, particularly the kazas of Anaselítsa, Grevená, and Elassón. During the 19th century they formed a quarter of the population of the Aliákmon Valley, according to the Epirote warrior of 1821, Lampros Koutsonikas . Zotos Molossos, a fellow Epirote, is more precise; he estimates them at 20 thousand and declares his bold opinion that within 24 hours of a successful revolution they would revert to Christianity.

SOURCE

Reassessing ethnic identity in the pre-national BalkansRaymond Detrez (Ghent University, KU Leuven)

Abstract Ethnic communities have been investigated so far mainly by anthropologists and ethnologists. As the specific research tools they have developed are not applicable to communities that have disappeared a long time ago, historians have searched for evidence of ethnic consciousness mainly in political statements, while literary historians have focused on egodocuments. However, a critical study of these and other written sources reveals that in the Balkans prior to the nineteenth century ethnic allegiance occupied a far more modest place in the hierarchy of moral values than is usually assumed. People identified with a religious community in the first place, to a large extent neglecting or ignoring ethnic distinctions and feeling no compelling moral liabilities regarding the ethnic community they belonged to. Obviously, religion is not a component of ethnic consciousness, as is so often claimed. Ethnic identity transpires to be rather a local variant of a larger, essentially religious collective identity. This state of affairs seriously challenges the traditional assumption that national communities organically “continue” ethnic communities.

(Pictured) "Young Greeks at the Mosque" (Jean-Léon Gérôme, oil on canvas, 1865); this oil painting portrays Greek Muslim recruits into the Ottoman Janissary corps at prayer in a mosque.

See also: Greek Muslims

Mavi Boncuk |

The Vallahades (Greek: Βαλαχάδες) or Valaades (Βαλαάδες) were a Greek-speaking, Muslim population who lived along the river Haliacmon in southwest Greek Macedonia, in and around Anaselitsa (modern Neapoli) and Grevena. They numbered about 17,000 in the early 20th century. They are a frequently referred-to community of late-Ottoman Empire converts to Islam, because, like the Cretan Muslims, and unlike most other communities of Greek Muslims, the Vallahades retained many aspects of their Greek culture and continued to speak Greek for both private and public purposes. Most other Greek converts to Islam from Macedonia, Thrace, and Epirus generally adopted the Turkish language and culture and thereby assimilated into mainstream Ottoman society.

The name Vallahades comes from the Turkish-language Islamic expression vallah ("by God!"). They were called so by the Greeks, as this was one of the few Turkish words that Vallahades knew. They were also called pejoratively "Mesimerides" (Μεσημέρηδες), because their imams, uneducated and not knowing much Turkish, announced mid-day prayer by shouting in Greek "Mesimeri" ("Noon"). Though some Western travellers speculated that Vallahades is connected to the ethnonym Vlach, this is improbable, as the Vallahades were always Greek-speaking with no detectable Vlach influences.

Ethnographic map of Macedonia (1892). Those defined as Greek Muslims are shown in yellow

The Vallahades were descendants of Greek-speaking Eastern Orthodox Christians from southwestern Greek Macedonia who probably converted to Islam gradually and in several stages between the 16th and 19th centuries.[6] The Vallahades themselves attributed their conversion to the activities of two Greek Janissary sergeants (Ottoman Turkish: çavuş) in the late 17th century who were originally recruited from the same part of southwestern Macedonia and then sent back to the area by the sultan to proselytize among the Greek Christians living there.

The Vallahades were resettled in western Asia Minor, in such towns as Kumburgaz, Büyükçekmece, and Çatalca, Kırklareli, Şarköy, Urla or in villages like Honaz near Denizli.[17] Many Vallahades still continue to speak the Greek language, which they call Romeïka[ and have become completely assimilated into the Turkish Muslim mainstream as Turks.

In contrast to the Vallahades, many Pontic Greeks and Caucasus Greeks who settled in Greek Macedonia following the population exchanges were generally fluent in Turkish, which they had used as their second language for hundreds of years. However, unlike the Vallahades, these Greek communities from northeastern Anatolia and the former Russian South Caucasus had generally either remained Christian Orthodox throughout the centuries of Ottoman rule or had reverted to Christian Orthodoxy in the mid-1800, after having superficially adopted Islam in the 1500s whilst remaining Crypto-Christians.

Even after their deportation, the Vallahades continued to celebrate New Year's Day with a Vasilopita, generally considered to be a Christian custom associated with Saint Basil, but they have renamed it a cabbage/greens/leek cake and do not leave a piece for the saint

Villages of the Vallahades around Anaselitsa SOURCE

Villages of the Vallahades around Anaselitsa SOURCEThere were pockets of them scattered amongst the Greek population of south-west Macedonia, particularly the kazas of Anaselítsa, Grevená, and Elassón. During the 19th century they formed a quarter of the population of the Aliákmon Valley, according to the Epirote warrior of 1821, Lampros Koutsonikas . Zotos Molossos, a fellow Epirote, is more precise; he estimates them at 20 thousand and declares his bold opinion that within 24 hours of a successful revolution they would revert to Christianity.

The Vallahades villages in the province of Anaselítsa totalled eighteen. In a number of these there still dwelt a few Christian families . Purely Moslem villages were the following: Pylorí, Lái (Peponiá), Yánkovi, Plazómista (Stavrodrómi), Váïpes (Dafnerón), Vínyani, Maxgáni,

Voudourína, Tsavalér, Tserapianí, Sirótsiani, Vróndriza (Vrondí). Of mixed populations were the following: Vrongísta, Tsotyli, Silomísti, Tsaknochóri, Rézni (Anthoúsa), Plázoumi (Homalí) . At Tsotyli, until the exchange of populations, there were about 150 Vallahades families and 40 Christian . There is a record, too, of a village called Ginós (Molócha), which was not far distant from Leipsísta (Neápoli). From Ginós there survives an ordinance of excommunication signed by the metropolitan of Sisanion Agathangelos. Though it does not bear a date, the document was clearly drawn up at a time when the inhabitants of the village were Christians, and is undeniable proof that the Vallahades of Ginós were of Christian origin .

In the Grevená region there were 17 villages of Greek-speaking Vallahades, of which 10 were entirely Moslem: Kríftsi (Kivotós), Dovrátovo (Vatólakkos), Goublár (Mersína), Meliá, Kyrakalí, Vrástino (Anávryta), Kástron, Pegadítsa, Agaléï of Véntzia, Tórista. The remaining 7 were mixed, namely Dovroúnitsa (Klimatáki), Soúbino (Kokkiniá), Trivéni (Sydendron), Dóvrani (Élatos), Véntzia (Kéntron) . Margaret Hardie (Mrs. Hasluck), who visited these villages earlier this century, writes: "In their houses also the Vallahades have retained their Christian taste, building as handsome a two-storeyed house as their means permit. The Asiatics build by preference an one-storeyed and let it straggle at will, apparently without any fixed plan... The general effect (of the Asiatics) is of secrecy and inhospitality so that, on going from the furtive Asiatics to the welcoming European Vallahades, I at least used to feel as if I had left a stuffy room and emerged into the fresh, wind-swept open"