Mavi Boncuk |

Mavi Boncuk |

Shaykh Muhammad ibn Mustafa al-Misri, Tuhfet ul-Mulk (a Turkish translation of Ruju al-shaykh ila sibah,

‘A Shaykh remembers his youth’), Turkey or Balkans, dated 1232 AH/1817 AD.

Ottoman Turkish manuscript on paper, 209 leaves, 29 lines to the page written in one and two columns in nasta’liq script, headings in red, with double inter-columnar rules in red, margins ruled in red, FOUR ILLUMINATED HEADPIECES with gold floral decoration and sixty-four pages with EIGHTY-FIVE MINIATURES ON VELLUM, including 39 FULL-PAGE, 45 HALF-PAGE AND ONE DOUBLE-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS, one printed map of the world inset, several vellum leaves laid down on paper, foliated in Persian throughout, gilt-stamped red morocco, each cover with a panel of padded black morocco.

33 by 22cm.

PROVENANCE

Sotheby’s, Fine Oriental Miniatures, Manuscripts and Qajar Paintings, London, 4 April 1978, lot 120.

Acquired in the above sale by a private collector

Purchased directly from the above in 1979/1980 by current owner.

EXHIBITED

Seduced: Art & Sex from Antiquity to Now, the Barbican centre, 12 October 2007 - 27 January 2008.

LITERATURE

Leoni and M. Natif (ed.), Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art, Farnham, 2013.

Wallace, M. Kemp and Bernstein, Seduced: Art & Sex from Antiquity to Now, London, 2007.

The Ottoman Erotic, episode 289 with Irvin Cemil Schickosted, Susanna Ferguson and Matthew Ghazarian, part of the Podcast series entitled 'Ottoman History Podcast':

SOTHEBYS Note

he contents of the text are summed up by a free translation of the title ‘A Shaykh remembers his youth’, namely a collection of fanciful reminiscences of the adventures and romances of an inquisitive man. Although the name of the patron is not included, it is clear from the quality and quantity of miniature paintings that this manuscript was commissioned by a member of the nobility, who carefully edited the text and possibly is portrayed in some paintings. Three dates are present in the manuscript, 1187 AH (1779 AD), 1214 AH (1799-80 AD) and 1232 AH (1817 AD), indicating that the manuscript took many years to complete and was carefully edited.

EROTIC LITERATURE IN OTTOMAN TURKEY

Ottoman erotic literature was a common genre and not frowned upon, as many today might mistakenly think. The genre of erotic literature developed from the sixteenth century onwards and erotic manuals, also known as bahname[1], were compiled and translated from various foreign traditions, mainly Persian and Arabic. Often these manuals were combined and integrated with others, making the identification of a single story or author very difficult. The vocabulary used in these manuals was also hybrid and a mix of different languages, with words imported from Arabic, Persian, Hindu, as well as more vulgar and popular sayings.

One of the most famous bahname in Ottoman times was titled Ruju' al-Shaykh ila Sibah fi al-Quwwah 'ala al-Bah (“The return on the old man to youth through the power of sex”). Originally based on an Arabic text from the thirteenth century[2], with a Persian translation as intermediary, this text was compiled and translated for the first time in Ottoman Turkish by the jurist Kemalpasa-zade (also known as Ibn-i Kemal Paşa) for Sultan Selim I in 1519; later versions of the same text were translated and adapted by other scholars.[3]

Erotic literature was usually accompanied by more or less explicit paintings, whose degree of graphicness depended on the period in which they were produced – Ottoman society was fairly permissive in the sixteenth century, more conservative in the seventeenth and quite liberal in the eighteenth – so manuscripts produced in this last period show vibrant and explicit scenes, sometimes of the finest nature. Our manuscript has an exceptional number of miniatures when compared with similar contemporaneous texts, and, uniquely, they are copied on vellum.

THE MANUSCRIPT

According to the introduction, this text is a compendium of several manuals. Although it started as a mere translation of the famed Ruju' al-Shaykh ila Sibah fi al-Quwwah 'ala al-Bah also known as Tuhfat al-Mulk (Tuhfetü'l-Mülk), the corpus was expanded to include other works (mainly three texts by Enderunlu Fazıl [4], the Hubanname, the Zenanname and the Çenginame) and presents itself as a sex manual divided into two sections, one dealing with men’s sexuality and the second concentrating on women. This volume is particularly exceptional for three aspects in particular: its size and its medium, the strong involvement of its editor(s) and patron, and the incredibly large amount of high quality paintings. Other contemporary erotic texts, which have either been offered on the open market or are currently in museum collections, are all of considerably smaller size, with fewer miniatures, and painted only on paper. [5]

This manuscript combines both vellum and paper, making it an incredibly rare and expensive production for its time. The use of vellum for all the paintings is quite an unusual choice and deserves further commentary. As a material, vellum is not the ideal choice for painting; it retains colors less and is more likely to get damaged on the verso. Considered an expensive and out-of-the-ordinary material for the time, one may understand why vellum was chosen to illustrate this manuscript, signalling its importance.

Although there is no dedication or named patron, we can infer from the size, use of expensive materials and quality of the miniatures, that this manuscript was reserved for the very high end of the market. Despite the fact that little is known about who read and used these manuals, several versions of the same text have survived, leading us to the conclusion that there was demand at different levels of society (with varying budgets). As noted by Shick[6], this manuscript is too accomplished to be a unique creation, but it is probably the top example of its kind.

The text has been written by more than one hand and completed at various stages: on f.205a two years are mentioned: one (in red) bears the date 1 Muharram 1187 AH (25 March 1779) and the city of Shumna (today Shumen, in north-east Bulgaria). This date refers to the completion of the first translation of the text Tuhfat al-Mulk, but it is not the final one.

The mention of the city of Shumna is worth noting: a prolific centre for calligraphy[7], its reference in our colophon attests to the fact that it was also probably a vibrant cultural center and the base for this first translation of the Persian original text.

The other date, below and in black, reads 15 H (probably read as Dhu’l-Haram) 1232 AH (26 October 1817). This date refers to the completion of the final translation and assembly of text. As mentioned above, this manual was not a mere transliteration from the Persian original, but was expanded and amplified with other manuals on human behavior.

The gap between the two dates in the colophon shows that this text has been carefully curated and it took the editor(s) more than four decades to complete. This long period and attention to details, along with some characters represented in the paintings -a point which we will analyse later in this essay- leads us to conclude that the commissioner was very much involved with the making and was keen to “customise” the text. A third date is also visible on the painting on f.83a where the year 1214 AH (1799-1800 AD) is written on the top right. The presence of a date on a painting leads us to assume that the corpus of illustrations commissioned to accompany the text was assembled over a long period of time (at least between 1799 and 1817 AD).

THE PAINTINGS

The paintings have been carefully integrated within the manuscript. While the hand that accompanies the pages with the paintings is different from the hand of most of the other pages, the editor(s) remained quite conscious of the need to integrate the paintings within the text, so pages were added to ensure the text flowed in its reading.

Multiple phases of completion for erotic manuscripts are not an anomaly. Two Hamse-i Atâyî, one in Istanbul (ref.no.5 at the end of this note) and one in Baltimore (ref.no.6 at the end of this note), both present later added miniatures: the colophon of the Hamse in Istanbul is dated 1691, but only one miniature is contemporaneous, while the other nine were added in the mid-eighteenth century.[8] The difference though in our case is that there is a conscious and deliberate choice of which paintings to include and the subject represented.

The Hamse in the Walters Collection in Baltimore presents two sets of miniatures, one contemporaneous with the text and the second painted around seventy years after the completion of the text. This second set of paintings is interestingly more explicit compared to the first set, but less integrated within the text[9] . In contrast, the editor of our manuscript has carefully inserted the paintings within the text, adding extra writing if necessary and making sure that the whole experience flows naturally, without blank pages interrupting the reading.

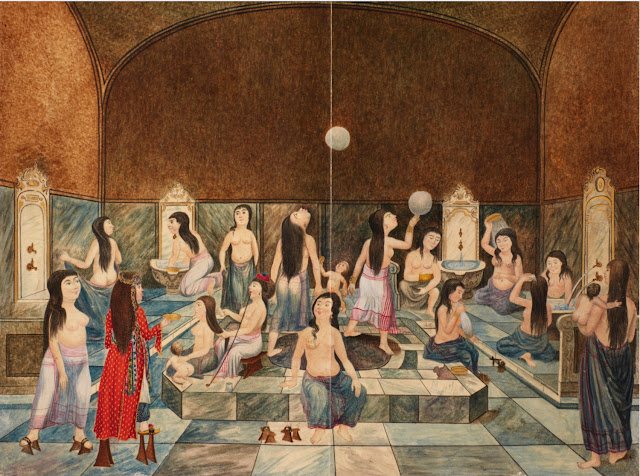

One of the most interesting aspects of this manuscript is the presence and combination within the volume of different styles of paintings which supports the hypothesis that different ateliers worked on the commission. The bifolium depicting women in the hammam (f.78b and 79a) strongly recalls a painting by Abdallah Bokhari now in the Library of Istanbul University (ref.no.8644/15)[10]. The delicate figures of the women in the illustrations on f.71b and 76a are similar to the ones in a Zenanamah dated 1206 AH (1793 AD), now in the Library of Istanbul University (ref.no.2824-7315). Opposed to this Ottoman painting tradition, the dynamism of other scenes, the costumes and the rendering of the natural setting all point towards a different tradition influenced probably by foreign schools as well. One hypothesis that would account for this combination of different styles within a single manuscript, could be that all of these miniatures were expressively commissioned by one single individual, who assembled them throughout more than a decade and wanted the liberty to choose and customise the text with his preferred paintings. If this was indeed the case, then the making of the manuscript was indeed very personal to the patron and commissioner.

To understand fully the context in which these paintings were produced, it is necessary to note that gender was not considered a dichotomy in Ottoman Turkey[11]. Three distinctive groups need to be identified when talking about sexuality: men, women, and male youths. The man is at the centre of the encounter most of the time, but there are occasions where only male youths or women are the principal protagonists. As noted by Shick, there is fluidity in gender: youths will become men, and the main distinction within a sexual act lies between who is passive and who is active. Heterosexual and homosexual (mainly male) scenes are both present in equal number, and often the encounter is interrupted or supervised by other people. An interesting illustration, worth noting, is the one on f.184a: the page is divided into two scenes representing two women having sex. Lesbian scenes were not as common, and these two examples are definitely a remarkable and quite out of the ordinary representation of single sex love.

SETTINGS AND COSTUMES

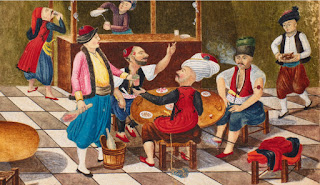

The settings are varied, and include natural bucolic scenes, with bushes, trees and animals (see illustrations on f.31a; 104a, 113a, 116a, 153a); more intimate and private encounters, in bedrooms and private rooms (see ill. on f.10a, 17a, 20a, 29, 51a, 111a and 112a), sometimes interrupted by a third party (see ill. on f.174a and 184b); while other scenes take place in public places, like a hammam (see ill. on f. 37a, 78b and 79a, 129b), a bakery (ill. f. 118a), or even a tomb (ill. f.115a). The scenes within architectural settings are incredibly detailed, especially f.82b and 83b which shows a rare night scene. Very few Ottoman paintings are set at night and this one is particularly remarkable for its finesse: a group of men stand in a courtyard holding lamps while a woman and a boy are visible through the windows, a delicate moon light also sheds some light on the scene. Another night scene is recorded in the Zenanname now in the British Library (Or.7094, f.51r), but the difference between the two paintings is striking, as in our miniature the effect of the lamp's light is visible in the projection of shadows on the wall and is definitely testament to the artist’s technical skill in rendering the contrast between light and darkness.

The varied representations of costumes throughout the entire manuscript deserve further and more detailed study. Each costume and outfit of the various characters depicted helps to identify not only their nationality, but also their class and social status. Dignitaries and princes are present, wearing a distinctive royal outfit, with a turban and a mantel (ill. f. 17a, 112a, 127a, 201a), as are members of the court, identifiable by distinctive turbans (ill. f.31a, 31b, 42a, 43b, 123a, 123b, 124a, 124b, 125a, 125b).

A set of paintings depicts homosexual encounters among members of the army, each with a very distinctive uniform (ill. f. 41b, 42a), and some clearly European. Characters in other scenes, more or less erotic, are wearing distinctively Austro-Hungarian costumes, while groups of women clearly look British, with dresses and shawls common in eighteenth-century Britain (ill. f.71b and 76b). Interestingly and noteworthing, as it is not found in any other erotic manuscript, is a painting representing a Sultan, possibly Mahmud II (r.1808-39) on f.201a.

The decision to include figures dressed in diverse fashions and costumes can be connected with a literary genre common at the time, which dealt with men and women of different continents and a general taste and curiosity for European habits and costumes. As noted by Renda, “the Ottoman sultans of the time were eager to establish political and economic relations with Europe. Ambassadors brought back new concepts that westernized the Ottoman courtly life and affected the tastes of the era, while a similar trend produced the wave of Turquerie in Europe.”[12] Along with the previously mentioned Hubanname ve Zenenname (The Book of Beautiful Men and Lovely Ladies) by Enderunlu Fazıl (d.1810), which describes men and women from all the continents and describes their physical look and outfits[13], some of the outfits strongly recall costume albums which were widely spread at the time. These compendia included images of figures of multiple nationalities and class, dressed in their most well known outfits. The main centre of production for these albums has been identified as Istanbul but European artists produced copies also in Britain and France. The album titled The Costume of Turkey, published in London by William Miller in 1804, is full of engravings depicting different members of the Ottoman society. From these engravings we can see some outfit which were clearly distinctive of a certain social class or role within the court, and many are clearly identifiable in our manuscript: the distinctive red dress, yellow-gold belt and tall red hat worn by the Silahdar Aga, sword bearer to the Sultan in this album[14] is the same worn by one of the men in the scene on f.128a.

THE PATRON

Another fascinating aspect of this manuscript is the presence in more than one miniature of the same character, similarly dressed and always wearing the same turban. The last leaf of the manuscript, after the colophon, bears a very interesting painting which is highly unusual for this context. It is a portrait of a standing man holding a bunch of flowers in his left hand and a black handkerchief in his right. He is probably in his late forties or early fifties, rather corpulent, with dark hair, pale skin, a small nose and very thin moustache. He is wearing a light blue coat, a striped shash around his waist, a white-dotted garment, red trousers and yellow shoes. Over his head he also wears a very distinctive turban, composed of a central dark blue base made of plisse, around which a white cloth is wrapped. The portrait is of fine quality and the only one of this kind in the manuscript, as the other scenes are mainly of erotic nature and always involve more than one character. When going through the paintings in the manuscript, one notices the same character, wearing an identical outfit, depicted in no less than three paintings, although he might be recognisable in other miniatures as well.

The first direct comparison with the standing figure is the man in f.34a, who is depicted seated in a restaurant eating fish while two women dance and a musician plays the violin. The seated man is wearing the same light blue coat, white-dotted vest, striped sash, yellow shoes and distinctive turban. His facial features are also very similar, pale and with a moon-shaped face, and the same thin moustache. There is no doubt in this instance that the two paintings depict the same individual. The same man is depicted on the lower painting on f.123a having a sexual encounter with a young man. Although he looks younger than in the other paintings, his facial features and clothes are identical. His appearance and turban are also similar to the man represented on f.124a. On f.128a our standing man is again present in an all-male group scene; although he is wearing a yellow vest (rather than a white-dotted one), all his other clothes, including the yellow shoes, are the same as the ones in the last painting on f.209a. Lastly, the same man, slightly older, is also represented on f.17a, in a heterosexual scene depicting him and a prostitute. He is wearing the usual red-trousers, yellow shoes, same turban, yellow vest and a more wintry blue coat with fur. Worth noting are also the facial features of the man in the hammam on f.37a, with a thin moustache, very pale skin and rounded face, all features which recall those of the standing figure, although due to the lack of clothes in the scene, this is a less obvious parallel.

The turban in all these scenes is quite distinctive. In the Costume of Turkey by Miller, this typology of turban, with a central base made of plisse, around which a white cloth is wrapped, is documented in the Ottoman court and each colour seems to be distinctive of a certain position within the palace: green plisse is associated with the ushers, the red plisse with the Sultan’s turban bearer and a dark blue, resembling the one worn by our standing man, with the Sultan’s private secretary.

Surely it is no coincidence that the same man is represented in more than one painting. Could it be that the man portrayed at the end of the manuscript is the commissioner? Could he have asked to be represented in some of the paintings? And, as these scenes involve officers from the Ottoman court, could it be that he himself was working for the Sultan?

CONCLUSION

This exceptionally rare manuscript is one of the most lavish copies of an erotic manual ever produced in Ottoman Turkey. Its large size, the use of expensive materials, and large amount of high quality paintings all point towards a high class of patron but also suggest that there was a market for erotic manuscripts throughout the Ottoman period. The hypothesis that it actually bears within it portraits of its patron is a unique feature found nowhere else in the known corpus of Ottoman illustrated literature[15].

EROTIC TEXTS SOLD THROUGH THE LONDON OPEN MARKET:

Sotheby's, London, 9 October 1978, lot 104

'Atai. Diwan, Turkish manuscript dated 1151 AH/1738 AD

“Turkish manuscript on paper, thirty contemporary Turkish miniatures, many of erotic nature”

25.8 by 14.5cm.

Christie's , London, 18 June 1998, lot 179

Tuhfat al-Mulk, Ottoman Turkey 1209 AH/1794-95 AD

“Turkish and occasional Arabic manuscript on polished buff paper, (…) with twenty full page miniatures, showing couples in amorous embrace and in various stages of nakedness.”

33 by 20.2cm.

Christie's, London, 17 April 2007, lot 293

Tuhfat al-Mulk, Ottoman Turkey circa 1750

“Ottoman Turkish on polished buff paper (…) with 50 miniatures showing couples in amorous embrace and various states of undress”

21.3 by 14.6cm.

EROTIC TEXTS IN MUSEUMS AND PUBLIC LIBRARIES:

British Library, London, inv. no. Or.13882

Hamse-i Atâyî, Istanbul dated 1151 AH/1738-39 AD; ink and colour on paper.

8.6 by 10.9cm.

Turkish and Islamic Art Museum, Istanbul, inv. no. Ms. 1969

Hamse-i Atâyî, Istanbul, 1103 AH/1691 AD; ink and colour on paper.

11.5 by 22.3cm.

Walters Art Gallery, Baltimore, MD, inv. no. W.666

Hamse-i Atâyî, Istanbul dated 1133 AH/1721 AD ink and colour on paper; 39 miniatures

11.5 by 11.8cm.

Topkapı Palace Museum, Istanbul, inv. no. R. 816

Hamse-i Atâyî, Istanbul, dated 1141 AH/1728 AD; in and colour on paper.

10.5 by 11.3cm.

John Frederick Lewis Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, inv. no. O.97

Hamse-i Atâyî, Istanbul, 1720-1730’s; ink and colour on paper.

15.3 by 10.9cm.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Atasoy, N., Turkish Miniature Painting, Istanbul, 1974.

Artan T. and Schick C. “Ottoman pornotopia: Changing visual codes in eighteen century Ottoman Erotic miniatures” in Leoni F. and Natif M. (ed.), Eros and Sexuality in Islamic Art, Farnham, 2013.

Bağci, Çağman, Renda and Tanını, Ottoman Painting, Ankara, 2010

Buturovic A. and Schick C., Women in Ottoman Balkans: Gender, Culture and History, London 2007.

Edhem F. and Stchoukine I., Les Manuscrits Orientaux Illustres de la Biblioteque de l’Universite de Stanboul, Paris, 1933.

Kangal S., The Sultan’s Portrait, Picturing the House of Osman, Istanbul, 2000.

Shama S., The Ottoman Turkish Zenanname (‘Book of Women’), published in November 2016 on the Asian and African Studies Blog of the British Library, London. Link: http://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-african/2016/11/the-ottoman-turkish-zenanname-book-of-women.html

Schick I. C., “Representation of Gender and Sexuality in Ottoman and Turkish Literature” in The Turkish Studies Association Journal, Vol. 2, N.1-2 (2004), pp.81-203.

Schick C., Ferguson S. and Ghazarian M., The Ottoman Erotic, episode 289, part of the Podcast series called Ottoman History Podcast.

Raby J., The Nasser Khalili Collection of Islamic Art: The Decorated Word, Qur’ans of the 17th to 19th century, London, 2009.

Renda G., “An Illustrted 18th century Ottoman Hamse in the Walters Art Gallery” in The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, Vol. 39 (1981), pp.15-32.

Wilkstrom T. , “Celebrating the Erotic Empire: Montfleury’s glorification of “Ottoman” Legal and Sexual Practices” in L’Esprit Createur, Vol.53, N.4, 2013, pp.71-83

[1] Bahname were both medical and erotic treatises at the same time, dealing with both the physiological aspects of sex such as contraception, cures and remedies or aphrodisiac recipes, as well as more explicitly erotic subjects as sexual positions. Artan and Schick, 2013, p.158.

[2] The original Arabic text was attributed to Ahmad bin Yūsuf al-Tifāshī (1184-1253). Artan and Schick, 2013, p.158.

[3] Artan and Schick record three further translations of this text, by Gelibolulu Mustafa Âli, ca. 1569; another version is recorded to have been offered to Na’tî Mîr Mustafa b. Hüseyin Paşa (d.1718) and a fourth one was translated at the same time by Mustafa Ebü’l Feyz et-Tabîb. Artan and Schick, 2013, p.159.

[4] Enderunlu Fazıl (1757-1810) also known as Fazıl Bey, lived in Istanbul at the end of the 18th century, during his stay at the Ottoman court he composed the Hubanname (Book of Beauties), a text describing different types of boys from all over the the world, and later its ‘sequel’, the Zenanname, on women.

[5] Please see the end of this essay for a list of erotic texts recorded in libraries and offered on the open market.

[6] The Ottoman Erotic, episode 289 with Irvin Cemil Shick, Susan Ferguson and Matthew Ghazarian, part of the Podcast series ‘Ottoman History Podcast’.

[7] Although most of the texts attributed to this area are of a religious nature, it is interesting to note that this city must have been a centre for manuscript production of different types, see Khalili 2009, p.222.

[8] Renda 1981, p.18.

[9] The original text is dated to the 1720-1730s and some miniatures are clearly comparable to a copy now in the Topkapı dated 1728 (7), while others are attributable to the end of the 18th century and painted on pages without text. Artan and Schick, 2013, p.164.

[10] Edhem and Stchoukine, 1933, p.23, fig.21.

[11] The Ottoman Erotic, episode 289 with Irvin Cemil Shick, Susan Ferguson and Matthew Ghazarian, part of the Podcast series Ottoman History Podcast.

[12] Renda, 1981, p.15.

[13] The only illustrated manuscript which includes both the Hubanname and Zenenname is dated 1206 AH/1793 AD, IUK, T.5502, Bağci, Çağman, Renda and Tanını, 2010, p.279.

[14] The full album is published online: http://world4.eu/costume-of-turkey/#Detail_The_costume_of_Turkey_by_Octavian_Dalvimart

[15] As this catalogue is being printed, Frankie Keyworth, MA student from SOAS is planning to make this manuscript the subject of her MA dissertation.