Mavi Boncuk |Washington Post | Opinions

The Turkey I no longer know

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. (Adem Altan/Agence France-Presse via Getty Images)

By Fethullah Gulen May 15 at 7:41 PM

Fethullah Gulen is an Islamic scholar, preacher and social advocate.

SAYLORSBURG, Pa.

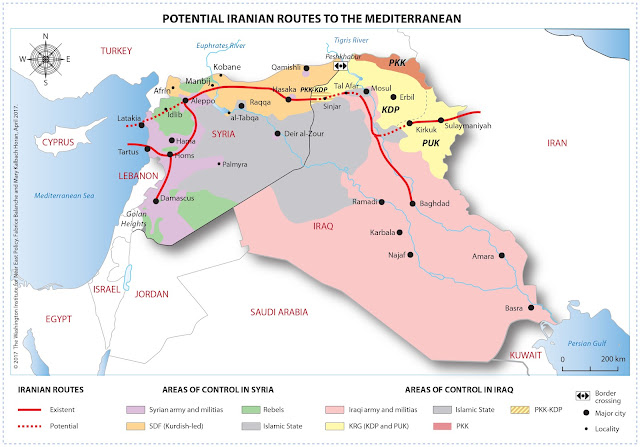

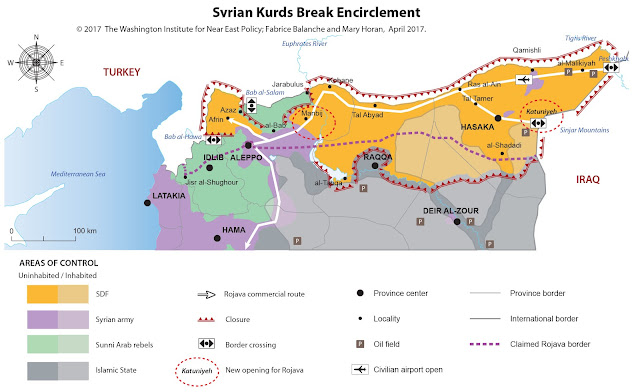

As the presidents of the United States and Turkey meet at the White House on Tuesday, the leader of the country I have called home for almost two decades comes face to face with the leader of my homeland. The two countries have a lot at stake, including the fight against the Islamic State, the future of Syria and the refugee crisis.

But the Turkey that I once knew as a hope-inspiring country on its way to consolidating its democracy and a moderate form of secularism has become the dominion of a president who is doing everything he can to amass power and subjugate dissent.

The West must help Turkey return to a democratic path. Tuesday’s meeting, and the NATO summit next week, should be used as an opportunity to advance this effort.

Since July 15, following a deplorable coup attempt, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has systematically persecuted innocent people — arresting, detaining, firing and otherwise ruining the lives of more than 300,000 Turkish citizens, be they Kurds, Alevis, secularists, leftists, journalists, academics or participants of Hizmet, the peaceful humanitarian movement with which I am associated.

As the coup attempt unfolded, I fiercely denounced it and denied any involvement. Furthermore, I said that anyone who participated in the putsch betrayed my ideals. Nevertheless, and without evidence, Erdogan immediately accused me of orchestrating it from 5,000 miles away.

The next day, the government produced lists of thousands of individuals whom they tied to Hizmet — for opening a bank account, teaching at a school or reporting for a newspaper — and treated such an affiliation as a crime and began destroying their lives. The lists included people who had been dead for months and people who had been serving at NATO’s European headquarters at the time. International watchdogs have reported numerous abductions, in addition to torture and deaths in detention. The government pursued innocent people outside Turkey, pressuring Malaysia, for instance, to deport three Hizmet sympathizers last week, including a school principal who has lived there for more than a decade, to face certain imprisonment and likely torture.

In April, the president won a narrow referendum victory — amid allegations of serious fraud — to form an “executive presidency” without checks and balances, enabling him to control all three branches of the government. To be sure, through purges and corruption, much of this power was already in his hands. I fear for the Turkish people as they enter this new stage of authoritarianism.

It didn’t start this way. The ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) came into power in 2002 by promising democratic reforms in pursuit of European Union membership. But as time went on, Erdogan became increasingly intolerant of dissent. He facilitated the transfer of many media outlets to his cronies through government regulatory agencies. In June of 2013, he crushed the Gezi Park protesters. In December of that year, when his cabinet members were implicated in a massive graft probe, he responded by subjugating the judiciary and the media. The “temporary” state of emergency declared after last July 15 is still in effect. According to Amnesty International, one-third of all imprisoned journalists in the world are in Turkish prisons.

Erdogan’s persecution of his people is not simply a domestic matter. The ongoing pursuit of civil society, journalists, academics and Kurds in Turkey is threatening the long-term stability of the country. The Turkish population already is strongly polarized on the AKP regime. A Turkey under a dictatorial regime, providing haven to violent radicals and pushing its Kurdish citizens into desperation, would be a nightmare for Middle East security.

The people of Turkey need the support of their European allies and the United States to restore their democracy. Turkey initiated true multiparty elections in 1950 to join NATO. As a requirement of its membership, NATO can and should demand that Turkey honor its commitment to the alliance’s democratic norms.

Two measures are critical to reversing the democratic regression in Turkey.

First, a new civilian constitution should be drafted through a democratic process involving the input of all segments of society and that is on par with international legal and humanitarian norms, and drawing lessons from the success of long-term democracies in the West.

Second, a school curriculum that emphasizes democratic and pluralistic values and encourages critical thinking must be developed. Every student must learn the importance of balancing state powers with individual rights, the separation of powers, judicial independence and press freedom, and the dangers of extreme nationalism, politicization of religion and veneration of the state or any leader.

Before either of those things can happen, however, the Turkish government must stop the repression of its people and redress the rights of individuals who have been wronged by Erdogan without due process.

I probably will not live to see Turkey become an exemplary democracy, but I pray that the downward authoritarian drift can be stopped before it is too late.

Mavi Boncuk |

Mavi Boncuk |