Infochart | July 24, 2018 General Elections

↧

↧

Word Origin | Emek

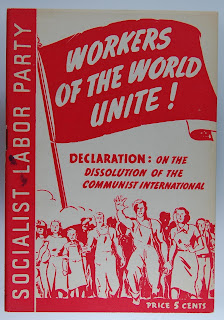

Text translation: 'The 1st of May. Workers of the world, unite!' Poster was produced in Russian in 1921.

Text translation: 'The 1st of May. Workers of the world, unite!' Poster was produced in Russian in 1921. Mavi Boncuk |

Emek: LaborEN [1] , work EN[2]from oldTR emge- acı çekmek +Ik oldTR (?) em ilaç +gA-

Historic source:

emgek "zahmet, eziyet, acı" [ Orhun Yazıtları (735) : Ok bodun emgek körti [Ok boyları zahmet çekti] ]

emgeklemek "dört ayak üstünde sürünmek" [ Uyghur c.1000 ]

emekli "zahmetli, zor" [ Meninski, Thesaurus (1680) ]

emekli "mütekâit" [ c (1935) : Emekli ve öksüzlerin ikinci altı aylık yoklamaları başlamıştır. ]

[1] labor (n.) c. 1300, "a task, a project" (such as the labors of Hercules); later "exertion of the body; trouble, difficulty, hardship" (late 14c.), from Old French labor "toil, work, exertion, task; tribulation, suffering" (12c., Modern French labeur), from Latin labor "toil, exertion; hardship, pain, fatigue; a work, a product of labor," a word of uncertain origin. Some sources venture that it could be related to labere "to totter" on the notion of "tottering under a burden," but de Vaan finds this unconvincing. The native word is work.

[1] labor (n.) c. 1300, "a task, a project" (such as the labors of Hercules); later "exertion of the body; trouble, difficulty, hardship" (late 14c.), from Old French labor "toil, work, exertion, task; tribulation, suffering" (12c., Modern French labeur), from Latin labor "toil, exertion; hardship, pain, fatigue; a work, a product of labor," a word of uncertain origin. Some sources venture that it could be related to labere "to totter" on the notion of "tottering under a burden," but de Vaan finds this unconvincing. The native word is work. Meaning "body of laborers considered as a class" (usually contrasted to capitalists) is from 1839; for the British political sense see labour. Sense of "physical exertions of childbirth" is attested from 1590s, short for labour of birthe (early 15c.); the sense also is found in Old French, and compare French en travail "in (childbirth) suffering" (see travail). Labor Day was first marked 1882 in New York City. The prison labor camp is attested from 1900. Labor-saving (adj.) is from 1776. Labor of love is by 1797.

labor (v.) late 14c., "perform manual or physical work; work hard; keep busy; take pains, strive, endeavor" (also "copulate"), from Old French laborer "to work, toil; struggle, have difficulty; be busy; plow land," from Latin laborare "to work, endeavor, take pains, exert oneself; produce by toil; suffer, be afflicted; be in distress or difficulty," from labor "toil, work, exertion" (see labor (n.)).

The verb in modern French, Spanish, and Portuguese means "to plow;" the wider sense being taken by the equivalent of English travail. Sense of "endure pain, suffer" is early 15c., especially in phrase labor of child (mid-15c.). Meaning "be burdened" (with trouble, affliction, etc., usually with under) is from late 15c. The transitive senses have tended to go with belabor. Related: Labored; laboring.

[2] work (n.) Old English weorc, worc "something done, discreet act performed by someone, action (whether voluntary or required), proceeding, business; that which is made or manufactured, products of labor," also "physical labor, toil; skilled trade, craft, or occupation; opportunity of expending labor in some useful or remunerative way;" also "military fortification," from Proto-Germanic *werkan "work" (source also of Old Saxon, Old Frisian, Dutch werk, Old Norse verk, Middle Dutch warc, Old High German werah, German Werk, Gothic gawaurki), from PIE *werg-o-, suffixed form of root *werg- "to do." Meaning "physical effort, exertion" is from c. 1200; meaning "scholarly labor" or its productions is from c. 1200; meaning "artistic labor" or its productions is from c. 1200. Meaning "labor as a measurable commodity" is from c. 1300. Meaning "embroidery, stitchery, needlepoint" is from late 14c. Work of art attested by 1774 as "artistic creation," earlier (1728) "artifice, production of humans (as opposed to nature)." Work ethic recorded from 1959. To be out of work "unemployed" is from 1590s. To make clean work of is from c. 1300; to make short work of is from 1640s. Proverbial expression many hands make light work is from c. 1300. To have (one's) work cut out for one is from 1610s; to have it prepared and prescribed, hence, to have all one can handle. Work in progress is from 1930 in a general sense, earlier as a specific term in accountancy and parliamentary procedure.

Work is less boring than amusing oneself. [Baudelaire, "Mon Coeur mis a nu," 1862]

Work and play are words used to describe the same thing under differing conditions. [attributed to Mark Twain]

work (v.)

a fusion of Old English wyrcan (past tense worhte, past participle geworht) "prepare, perform, do, make, construct, produce; strive after" (from Proto-Germanic *wurkijan); and Old English wircan (Mercian) "to operate, function, set in motion," a secondary verb formed relatively late from Proto-Germanic noun *werkan (see work (n.)).

Sense of "perform physical labor" was in Old English, as was sense "ply one's trade" and "exert creative power, be a creator." Transitive sense "manipulate (physical substances) into a desired state or form" was in Old English. Meaning "have the expected or desired effect" is from late 14c. In Middle English also "perform sexually" (mid-13c.). Related: Worked (15c.); working. To work up "excite" is from c. 1600. To work over "beat up, thrash" is from 1927. To work against "attempt to subvert" is from late 14c.

↧

Orkhon Text | 𐰢𐰏𐰚 Emgek (Emek)

Orkhon is sometimes called Turkic Runes because of their angular shape, and there are enough similarities to Futhark

Mavi Boncuk |

𐰾𐰇𐰚𐰼𐱅𐰢𐰕: 𐰉𐱁𐰞𐰍𐰍: 𐰘𐰰𐰇𐰦𐰼𐱅𐰢𐰕: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰏𐰾: 𐰴𐰍𐰣: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰𐰢: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣𐰃𐰢: 𐰼𐱅𐰃: 𐰋𐰃𐰠𐰢𐰓𐰇𐰚𐰤: 𐰇𐰲𐰇𐰤: 𐰋𐰃𐰕𐰭𐰀: 𐰖𐰭𐰞𐰑𐰸𐰃𐰤: 𐰖𐰕𐰃𐰦𐰸𐰃𐰤: 𐰇𐰲𐰇𐰤: 𐰴𐰍𐰣𐰃: 𐰇𐰠𐱅𐰃: 𐰉𐰆𐰖𐰺𐰸𐰃: 𐰋𐰏𐰠𐰼𐰃: 𐰘𐰢𐰀: 𐰇𐰠𐱅𐰃: 𐰆𐰣: 𐰸: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣: 𐰢𐰏𐰚: 𐰚𐰇𐰼𐱅𐰃: 𐰲𐰇𐰢𐰕: 𐰯𐰀𐰢𐰕: 𐱃𐰆𐱃𐰢𐰾: 𐰘𐰃𐰼: 𐰽𐰆𐰉: 𐰃𐰓𐰾𐰕: 𐰴𐰞𐰢𐰕𐰆𐰣: 𐱅𐰃𐰘𐰤: 𐰕: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣𐰍: 𐰃𐱅𐰯: 𐰖𐰺𐱃𐰯: ----: 𐰉𐰺𐰽: 𐰋𐰏:

SÖKüRTüMiZ: BaŞLıGıG: YÜKÜNDüRTüMiZ: TÜRGiŞ: KAGaN: TÜRÜKüM: BUDuNIM: eRTİ: BİLMeDÜKiN: ÜÇÜN: BİZiŊE: YaŊıLDUKIN: YaZINDUKIN: ÜÇÜN: KaGaNI: ÖLTİ: BUYRUKI: BeGLeRİ: YiME: ÖLTİ: ON: OK: BODuN: eMGeK: KÖRTİ: eÇÜMiZ: aPAMıZ: TUTMıŞ: YİR: SUB: İDiSiZ: KaLMaZUN: TİYiN: aZ: BODuNıG: İTiP: YaRaTıP: ----: BarS: BeG:

çöktürdük, başlıyı yükündürdük. Türgiş kağanı Türk'üm boylarım idi. Bilemediği için, bize yanıldığı, yazındığı için kağanı öldü. Buyruğu, beğleri yine öldü. On Ok boyları emek gördü. eçümüzün apamızın tutmuş [olduğu] yer su ıssız kalmasın diye Az boylarını eğitip, yaratıp ---- Bars Beğ

Mavi Boncuk |

𐰾𐰇𐰚𐰼𐱅𐰢𐰕: 𐰉𐱁𐰞𐰍𐰍: 𐰘𐰰𐰇𐰦𐰼𐱅𐰢𐰕: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰏𐰾: 𐰴𐰍𐰣: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰰𐰢: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣𐰃𐰢: 𐰼𐱅𐰃: 𐰋𐰃𐰠𐰢𐰓𐰇𐰚𐰤: 𐰇𐰲𐰇𐰤: 𐰋𐰃𐰕𐰭𐰀: 𐰖𐰭𐰞𐰑𐰸𐰃𐰤: 𐰖𐰕𐰃𐰦𐰸𐰃𐰤: 𐰇𐰲𐰇𐰤: 𐰴𐰍𐰣𐰃: 𐰇𐰠𐱅𐰃: 𐰉𐰆𐰖𐰺𐰸𐰃: 𐰋𐰏𐰠𐰼𐰃: 𐰘𐰢𐰀: 𐰇𐰠𐱅𐰃: 𐰆𐰣: 𐰸: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣: 𐰢𐰏𐰚: 𐰚𐰇𐰼𐱅𐰃: 𐰲𐰇𐰢𐰕: 𐰯𐰀𐰢𐰕: 𐱃𐰆𐱃𐰢𐰾: 𐰘𐰃𐰼: 𐰽𐰆𐰉: 𐰃𐰓𐰾𐰕: 𐰴𐰞𐰢𐰕𐰆𐰣: 𐱅𐰃𐰘𐰤: 𐰕: 𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣𐰍: 𐰃𐱅𐰯: 𐰖𐰺𐱃𐰯: ----: 𐰉𐰺𐰽: 𐰋𐰏:

SÖKüRTüMiZ: BaŞLıGıG: YÜKÜNDüRTüMiZ: TÜRGiŞ: KAGaN: TÜRÜKüM: BUDuNIM: eRTİ: BİLMeDÜKiN: ÜÇÜN: BİZiŊE: YaŊıLDUKIN: YaZINDUKIN: ÜÇÜN: KaGaNI: ÖLTİ: BUYRUKI: BeGLeRİ: YiME: ÖLTİ: ON: OK: BODuN: eMGeK: KÖRTİ: eÇÜMiZ: aPAMıZ: TUTMıŞ: YİR: SUB: İDiSiZ: KaLMaZUN: TİYiN: aZ: BODuNıG: İTiP: YaRaTıP: ----: BarS: BeG:

çöktürdük, başlıyı yükündürdük. Türgiş kağanı Türk'üm boylarım idi. Bilemediği için, bize yanıldığı, yazındığı için kağanı öldü. Buyruğu, beğleri yine öldü. On Ok boyları emek gördü. eçümüzün apamızın tutmuş [olduğu] yer su ıssız kalmasın diye Az boylarını eğitip, yaratıp ---- Bars Beğ

↧

15 Mayıs 1984 Aydınlar Dilekçesi

Aziz Nesin[1] öncülüğünde bir grup aydın, kendi aralarında organize ettikleri çeşitli toplantılar sonucunda “Türkiye’de Demokratik Düzene İlişkin Gözlem ve İstekler” başlıklı bir dilekçe hazırlarlar. Dilekçe imzaya açılır ve tam 1260 kişi imzalar.

Aziz Nesin[1] öncülüğünde bir grup aydın, kendi aralarında organize ettikleri çeşitli toplantılar sonucunda “Türkiye’de Demokratik Düzene İlişkin Gözlem ve İstekler” başlıklı bir dilekçe hazırlarlar. Dilekçe imzaya açılır ve tam 1260 kişi imzalar. 15 Mayıs 1984 günü Cumhurbaşkanlığına ve TBMM Başkanlığına sunulan tarihi dilekçe. 20 Mayıs 1984 günü Ankara Sıkıyönetim Komutanlığı tarafından dilekçeciler hakkında “yasadışı bildiri hazırlayıp dağıtmaktan” dolayı soruşturma başlatılır.

59 kişi hakkında dava açılır.

“Sıkıyönetim yasaklarına aykırı olarak bildiri dağıtmak” suçundan Ankara 1 no.lu Sıkıyönetim Mahkemesi’nde görülen, 18 Ağustos 1984 tarihinde ilk duruşması yapılan dava, 7 Şubat 1986'da tüm sanıklar için beraatle sonuçlanır.

Mavi Boncuk |

AŞAĞIDA İMZASI BULUNANLARIN TÜRKİYE’DE DEMOKRATİK DÜZENE İLİŞKİN

GÖZLEM VE İSTEKLERİ

Demokrasi, kurumları ve ilkeleri ile yaşar. Bir ülkede demokrasinin temel harcını oluşturan kurum, kavram ve ilkeler yıkılırsa bunun zararlarını gidermek güçleşir

.

Demokrasiyi kendi öz değer ve kurumlarına yabancılaştırmak, biçimsel olarak koruyup içeriğini boşaltmak, onu yıkmak kadar tehlikelidir. Bu nedenlerle tarihsel birikime dayalı devlet yapımızı ayakta tutan kurum, kavram ve ilkelerin korunmasını ve demokratik ortam içinde güçlenmesini savunmaktayız.

Halkımız, Çağdaş toplumlarda geçerli insan haklarının tümüne layıktır ve bunlara eksiksiz olarak sahip olmalıdır. Ülkemizin, insan haklarının güvenceleri yurt dışında tartışılır bir ülke durumuna düşürülmüş olmasını onur kırıcı buluyoruz.

Yaşam hakkı ve insanca yaşama, örgütlü ve toplumsal var olmanın çağımızda hiçbir gerekçe ile ortadan kaldırılamayacak baş amacıdır; doğal ve kutsal bir haktır. Bu hakkın anlam kazanması, düşünceyi özgürce açıklamaya, geliştirmeye ve etrafında örgütlenmeye bağlıdır. Bireylerimizin yeni ve değişik düşünce üretmelerini, gösterilmeye çalışıldığı gibi, bunalımların nedeni değil, toplumsal canlılığın gereği sayıyoruz.

İnsanların son sığınağı olan adalet, insanca yaşamın da başlıca dayanağıdır. Bun gerçekleşmesinin çağdaş hukuk devletinde geçerli yolları, adalet arayışının hiçbir şekilde engellenmemesi ve adalete ulaşmada olağanüstü yargı yollarına ve olağandışı yöntemlere başvurulmamasını gerektirmektedir. Olağanüstü yönetim bicilerinin olağan sayılan dönemlerde süreklilik kazanmasının demokrasi anlayışı ile bağdaşmayacağı görüşündeyiz.

Yargı kararı olmaksızın yurttaşların haklarının kısılması, tartışılması mümkün olmayan tek yanlı idari işlemlerle suç oluşturulması, siyasal hakların ellerden alınması ve genel suçlamalar yapılması, toplumsal yıkımlara yol açmaktadır. Dernek, kooperatif, vakıf, meslek odaları, sendika ve siyasal partilere girmenin ve açıklandığı zaman suç sayılmayan düşüncelerin sonradan egemen anlayışa göre, suç sayılması hukuk devleti kavramıyla bağdaşmaz.

Türkiye’nin yaşadığı yoğun terör eylemlerinden demokratik sistemin kendisi sorumlu tutulamaz.

Her örgütlü toplumun şiddet eylemleriyle mücadele etmesi kaçınılmaz görevidir. Ancak, devlet olmanın temel niteliği, terörle mücadelede hukuk ilkelerine bağlı kalmaktır. Terörün varlığı hiçbir zaman, devletin de aynı yöntemlere başvurmasının gerekçesi olamaz.

Varlığı yasal kararlarla da kanıtlanan işkence insanlığa karşı suçtur. İşkencesin yargısı, peşin ve ilkel bir cezalandırma alışkanlığına dönüştürülmüş olmasından endişe ediyoruz. Ayrıca, özgürlüğü sınırlama amacını aşan cezaevi koşullarını da eziyet ve işkence sayıyoruz.

İşkencenin büsbütün ortadan kaldırılması için gerekli önlemler alınmalıdır. Savunma, soruşturma ve kovuşturmada, hukuk devleti kuralları dışına çıkılır ve yargısal yöntemlerde en başta sanık makum oluncaya kadar masumdur ilkesiyle vurgulanan evrensel güvenceler yok sayılırsa, keyfilik, özellikle siyasal davalarda yargılamanın temel unsurlarından biri olur.

Terör eylemlerinin oluşmasında toplumun bütün kesimlerinin sorumluluk payı olduğu göz önüne alınarak, ölüme dayalı çözüm düşüncesinin ortadan kaldırılması için kesinleşmiş idam kararlarının infazlarının durdurulması ve ölüm cezalarının kaldırılması gereğine inanıyoruz.

Gecikmiş adaletin adaletsizlik olduğu evrensel gerçeğine dayanarak, görülmekte olan davaların bir an önce sonuçlandırılması gerektiği görüşündeyiz.

Suçları oluşturan, toplumsal ve siyasal koşullardır. Türkiye’nin içinde yaşadığı çalkantılı dönemin topluma yüklediği sorumluluk unutulmamalıdır. Bu nedenlerden ötürü ve sosyal barışa katkıda bulunmak için kapsamlı bir affı kaçınılmaz görüyoruz.

Kamu yaşamında iyiyi kötüden, doğruyu yanlıştan ayırmanın yolu olan siyaset, toplumun tümünün yönetime katılmasıdır. Güncel siyasetin her ülkede görülen ve kaçınılmaz olan aksaklıkları, herkese açık gereken siyaset yoluyla topluma hizmetin engellenmesinin ve belirli zümrelerin, kişinin ve kişilerin tekeline bırakılmasının nedeni olamaz. Siyaset yalnızca idari kararlara indirgenemez.

Milli irade ancak, toplumun bütün kesimlerinin özgürce örgütlenebildiği düzenlerde anlam ifade eder. Kimsenin siyasal kanı ve felsefi düşüncesinden ötürü suçlanmadığı, hiçbir yurttaşın dinsel inançlarından dolayı kınanmadığı ülkelerde milli irade en üstün güçtür. Bu üstün gücün meşruluğu, temel hak ve özgürlüklere karşı takındığı tavra bağlıdır.

Çoğunluk iradesinin özgürce belirlenmesini engelleyen koşullar demokrasiye aykırıdır. Bunun gibi, çoğunluk iradesini bahane ederek temel hakları yok etmek de demokrasi ile bağdaşmaz.

Tarihsel gelişim süreci içinde demokratik anayasaların amacı, kişi hak ve özgürlüklerini güvence altına almaktır. Bireyi devlet karşısında güçsüzleştiren düzenlemeler, hangi ad altında getirilirse getirilsin, demokrasiden uzaklaşma anlamına gelir. Bu durumda, demokratik yaşamın kaynağı olması gereken anayasa, demokrasinin engeli olur.

Başta siyasi partiler olmak üzere, sendikalar, mesleki kuruluşlar ve dernekler, demokratik yaşamın vazgeçilmez dayanaklarıdır. Mesleki örgütlenmeler, üyelerin dayanışma ve ekonomik çıkarlarını savunmakla görevli oldukları kadar, siyasi partilerle birlikte, birey ve grupların demokratik özgürlüklerimi korumanın ve yönetime katılmalarının aracı ve etkeni de olmalıdır. Bu nedenle, örgütlenme ve katılım haklarının anayasal düzenlemeler içinde en geniş güvencelere kavuşturulması gerektiğine inanıyoruz.

Bir toplumun yaşayışında, özgürlük, çeşitlilik ve yenilik öğelerinin bulunması, toplumun geleceği ve gelişmeye açık tutulması için zorunludur. Bu bakımdan her türlü düşünce üretimi korunmalı, yeni önerile kamuya özgürce sunulabilmelidir.

Özgür basın, demokratik düzeni bütünleyen temel öğelerden biridir. Bunun sağlanması için, bağımsız, denetimsiz ve çok yanlı olarak toplumun kendinden haberli olması, değişik düşüncelerin özgürce yansıtılması ve her türlü eleştirinin basında yer bulması zorunludur. Çok yönlü kamuoyu oluşması ve yönetimin demokratik denetimi ancak böyle bir basınla gerçekleştirilebilir. Yine bu nedenlerle ve yansızlığın önkoşulu olarak TRT’nin de özerkliğinin sağlanması gerektiğine inanıyoruz.

Eğitimin temel amacı, özgür düşünceli, bilgili, becerli ve üretici insan yetiştirmektir. Bunun tersine, tek tip insan yaratmaya çalışmak, çağdaş gelişmeler ve çoğulcu demokrasiyle bağdaşmaz. Çağdaş demokrasi, dünyaya eleştirel gözle bakabilen insan yetiştirmeyi amaçlar.

Toplumun en yetişkin kesimi olan üniversitelerin özerklikten yoksun bırakılarak kendi kendilerini yönetmeye layık olmadıklarının ileri sürülmesi, ülkemizde demokrasinin işleyebileceğini inkar etmek anlamına gelir. Bütün yüksek öğretim kurumlarının, atamalarla oluşturulan aşırı yetkili bir kurulun buyruğuna verilmesi, hem gençlerin iyi yetiştirilmesini, hem de bilim yapılmasını şimdiden engellediği gibi ülkenin geleceği için büyük kaygılar doğurmaktadır. Bu nedenle, YÖK düzeninin bir an önce seçim ilkesine dayalı özerklik yönünde değiştirilmesini gerekli görüyoruz.

Fikir ve sanat özgürlüklerinin serbestçe oluşmasını engelleyen hukuki ve fiili sınırları kaldırmak ve her yurttaşla birlikte, düşünce ve sanat adamlarını da genel güvencelerle donatmanın bir uygarlık koşulu olduğunu önemle belirtmek isteriz. Sağlıklı bir toplumsal gelişme, her türlü sanat yapıtlarının üretiminde ve yayımında özgürlüğü, kültürel yaratıyı son derece sınırlayan sansürün toptan kaldırılmasını, hiçbir konunun tabu haline getirilmemesini, ceza sorumluluğunun yalnız olağan yargı mercilerince saptanmamasını gerektirir.

Bütün bunların ışığında, topluma karşı sorumluluklarının bilincinde olan bizler, çağdaş demokrasinin, ayrı ayrı ülkelerin özel koşullarına göre uygulamadaki değişikliklere karşın, değişmeyen bir özü olduğuna bu özü oluşturan kurum ve ilkelerin bizim ulusumuzca da benimsenmiş bulunduğuna, bunlara aykırı düşen yasal düzenleme ve uygulamaların demokratik yöntemlerle ortadan kaldırılması gerektiğine, yaşadığımız bunalımdan, böylelikle, sağlıklı ve güvenli olarak çıkılacağına olanca içtenliğimizle inanmaktayız.

Haklarında Dava Açılan İmza Sahipleri

Aziz Nesin, Hasan Gürsel, İlhan Tekeli, Uğur Mumcu, Erbil Tuşalp, Haluk Gerger, Bahri Savcı, Yalçın Küçük, Mahmut Öngören, Mete Tunçay, Şerafettin Turan, Yakup Kepenek, Murat Belge, Halit Çelenk, Mehmet Emin Değer, Korkut Boratav, Mustafa Ekmekçi, Tahsin Saraç, Nurkut İnan, İnci Aral, Güler Tanyolaç, Güngör Aydın, Haldun Özen, Haki Bülent Tanık, Güngör Dilmen, Gencay Gürsoy, Vedat Türkali, Özay Erkılıç, Salih Şencan, Kemal Demirel, Vecdi Sayar, Tullui Sönmez, Onat Kutlar, İlhan Selçuk, Ümit Erdoğan, Berna Moran, Minu İnkaya, Veli Lök, Emre Kapkın, Cahit Tanör, Yılmaz Tokman, Şinasi Acar, Ali Oralp Basım, Ruşen Hakkı Özpençe, Hayri Tütüncüler, Güngör Türkeli, Atıf Yılmaz, Başar Sabuncu, Orhan Ş. Balcıoğlu, Erdal Öz, Turgut Kazan, Talat Mete, Ercan Ülker, Ahmet Kocabıyık, Ali Cumhur Ertekin, Yılmaz Polat, Gürsoy Dinç, Cemal Nedret Erdem, Muhittin Yavuz Aksu

[1] Aziz Nesin'in Aydınlar Dilekçesi Öyküsü | Emre Kongar

Aziz Nesin toplumsal sorumluluk bilinci çok gelişmiş bir yazardı.

Toplumsal bilimlere de büyük bir ilgi duyardı.

Bu açıdan en beğendiği yapıtı Surnâme adlı romanıydı.

Bilindiği gibi Surnâme, Divan Edebiyatı'nda şenlik, düğün şenliği, sünnet düğünü, ziyafet gibi olayların anlatıldığı, minyatürlerle de desteklenen manzum bir biçimdir.

Bu romanda Aziz Bey, bir idam mahkûmunun öyküsü bağlamında Türkiye'nin toplumsal yapısını, bireyi suça iten faktörleri, insanı ve hukuk düzenini irdeler.

İlk tanıştığımızda bana hemen bu kitabını okuyup okumadığımı sormuş ve "Hayır" yanıtını alınca derhal okumamı önermişti.

Sanıyorum beni sevmesinin ve dostluğuna kabul etmesinin önemli nedenlerinden biri toplumbilimci olmamdı.

Ankara'da başlayan dostluğumuz, ben 12 Eylül'ün üniversitelerdeki uygulamalarını YÖK bağlamında protesto etmek için ve bardağı taşıran son damla olarak sakalımı kesmeye zorlandığımdan dolayı istifa ettikten sonra, geldiğimiz İstanbul'da artarak devam etti.

* * *

Aziz Bey 12 Eylül'ün baskıcı rejiminden çok rahatsız olmuştu ve mutlaka bir şeyler yapmak gereksinimi hissediyordu; sonunda, yapılan yanlışlara aydınlar tarafından imzalanan bir dilekçe ile karşı çıkmaya karar vermişti.

Tarihe "Aydınlar Dilekçisi" olarak geçen bu olayın başında beni aradı ve evine çağırdı:

O sırada Hürriyet'te çalışıyordum...

Aziz Nesin de Nişantaşı'ndaki evinde kalıyordu.

Gittiğimde hemen konuya girdi, projesini açıkladı.

Dilekçeyi imzalamasını düşündüğü kişilerle, metni hazırlamak üzere derhal toplantılar yapmaya başlamak istiyordu...

Ve bana bu projenin götürücülüğünü önerdi.

Sanıyorum, hazırlanacak dilekçenin, kendisi dışında, özellikle akademisyenlerden ve gazetecilerden oluşan bir grup tarafından benimsenmesini planlamıştı.

* * *

Bu serüveni "Yaşamın Anlamı" kitabımda uzun uzun anlattım; olayı ve o dönemi merak edenler mutlaka okumalıdır.

Bugünkü sahte kahramanların çoğu o sıralarda 12 Eylül'e dalkavukluk etme yarışındayken Aziz Nesin ve bir avuç aydın, darbenin güçlü adamı Kenan Evren'e verilmek üzere "Türkiye'de Demokratik Düzene İlişkin Gözlem ve İstemler" başlıklı bir protesto ve istek dilekçesi hazırlıyordu.

Hürriyet'teki sorumluklarımdan dolayı proje götürücülüğünü kabul edemedim ama, hazırlık toplantılarına katıldım ve Aziz Bey'le birlikte, metnin tamamına yakın büyük bir bölümünün redaksiyonunu yaptım.

Metin toplantıları genellikle Nişantaşı'ndaki evde oluyordu ve katılımın olanaklı olduğu ölçüde genişletilmesi için, her toplantıya değişik kişileri çağırıyorduk.

Sonunda ortaya çıkan ve üzerinde mutabakat sağlanan metni 1383 kişi imzaladı.

Aziz Bey, Hacettepe Üniversitesi'nin değerli göğüs cerrahı Prof. Hüsnü Göksel'le birlikte Çankaya'ya çıkarak dilekçeyi Evren'e vermek istedi; Evren kabul etmediği için kapıya bırakıp çıktı.

Sonradan İstanbul Sıkıyönetim Savcılığı bütün imzacılar hakkında soruşturma açtı ve hepimizi Selimiye kışlasına celbedip ifadelerimizi aldı.

Bu sırada dilekçeyi, konut kooperatifi üyeliği sanıp imzaladıklarını "açıklayanlar" da oldu...

Ayrıntılar "Yaşamın Anlamı"nda.

Öyle bir dönemdi işte!

↧

Bernardino Nogara | Europe’s great tragedy seen through a man’s letters to his wife

Mavi Boncuk | SOURCE

Intesa Sanpaolo Group Historical Archives via Morone 3 (reading room) largo Mattioli 5 (postal address) 20121 Milan tel. +39 02 87942970 archivio.storico@intesasanpaolo.com

Bernardino Nogara

The Galata Bridge in Constantinople; photo taken between 1908 and 1914

(Nogara Family Archive)

NO. 1 SEPTEMBER 2016 page 5

Europe’s great tragedy seen through a man’s letters to his wife Francesca Pino

She and their children had returned to Italy alone following a nearly decade-long stay in Istanbul, where Nogara worked for Banca Commerciale Italiana (BCI) as director of the Eastern Trading Company (Società Commerciale d’Oriente – COMOR); they ended up staying there due to the outbreak of WWI. The letters span a period of just over a year, from 2 July 1914 through 11 July 1915, just prior to Italy’s declaration of war on Turkey in August 2015. The book contains a single letter by Ester – the only one that has survived – dated 23 May 1915, the day that news got around of Italy’s entry into the war. It is found in the appendix for this reason. Bernardino Nogara[1] was a prominent figure in twentieth-century history. A liberal Catholic from an ancient Lombard family, he held a degree in mining engineering from the Milan Polytechnic and acted as BCI’s representative in the Mediterranean and Eastern European regions. A financier, he was also tasked with diplomatic responsibilities, and following the 1929 Concordat between the Vatican and Italy he became the first Director of the Special Administration of the Holy See. He was also a member of BCI’s board of directors from 1925 to 1945 when, thanks to his active participation in the National Liberation Committee in Rome, he was appointed the bank’s vice president on 28 June. He held that position until his death in 1958.

The correspondence is intriguing from several perspectives. First of all, it lets readers reconstruct the sequence of declarations of war between the various countries, which were bilateral and staggered over time. It also provides an understanding of the ambiguous behavior towards Russia of the Turks, who sided with Germany early on, allowing two German submarines to enter the Bosphorus. Bernardino Nogara’s reading of events is both diplomatic and highly perceptive, capturing the atmosphere of mistrust that developed within the international community following the entry into war of various countries. He had decided to stay on in Istanbul since a minimum number of board members was required to manage the administration of the Ottoman public debt. The letters show how Nogara grew increasingly convinced as time went by of the need for Italy to enter the war and subsequently to be able to claim the unredeemed lands (Trento and Trieste). He makes observations on the behavior of foreign ambassadors and Turkish ministers to his wife, who was herself quite familiar with that milieu; indeed, she had played a representative role that was very much appreciated by Italy’s ambassador in Constantinople, Camillo Garroni. Nogara’s comments convey the increasingly heavy atmosphere in the city, and the sense of isolation felt by the few Europeans still resident there.

At one point Nogara undertook a several day-long journey by ship and on horseback to visit the Heraclea mines in Anatolia, and then returned to Italy through Sofia and Thessaloniki, having obtained permission to visit his family in Bellano on Lake Como. Once in Italy he was called back repeatedly to carry out a range of diplomatic missions and assignments both for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and for BCI and Otto Joel, the bank’s co-founder and director. Nogara’s writing style is eloquent yet terse, circumspect rather than rhetorical; indeed, his letters were often opened for censure. They include fascinating discussions of the growing difficulties of the postal and telegraph links, but also touch on more intimate, family-related matters such as the couple’s home, their garden, the care of plants and Nogara’s love for his wife. The elegant layout of the book and its exceptional selection of photographs (thanks to the analytical cataloguing done by Serena Berno, an Intesa Sanpaolo Group Historical Archives staff member) help readers to fully immerse themselves in the events of the period.

Published with the support of Intesa Sanpaolo, the book includes an introduction by Marta Petricioli on Italy’s foreign policy in the Mediterranean region, and on the role played by the aforementioned Società Commerciale d’Oriente, which also carried out banking business in Istanbul and other Mediterranean cities.

Lettere da Costantinopoli (1914-1915). Carteggio familiare di Bernardino Nogara [Letters from Constantinople (1914-1915). The Family Correspondence of Bernardino Nogara], edited by Bernardino Osio with an introduction by Marta Petricioli, Florence, Centro Di, 2014 (174 pages).

All credit for this elegant and absorbing volume – Lettere da Costantinopoli (1914- 1915). Carteggio familiare di Bernardino Nogara – is due to Bernardino Osio, a former ambassador, who conceived and edited it. It contains a brief part of the substantial correspondence between his grandfather, Bernardino Nogara, and Nogara’s wife, Ester Martelli.

Ambassador Bernardino Osio, grandson of Nogara, has his diary at his family archive in Rome. The diary has not so far been published, but has been used in two previous scholarly works: Renzo De Felice used extracts from the diary in his article, 'La Santa Sede e il conflitto italo-etiopico nel diario di Bernardino Nogara', Storia Contemporanea, 4 (1977), pp 823-34, and

Giovanni Belardelli published an important, attached document, the journal of Nogara's visit to the United States in 1937,'Un viaggio di Bernardino Nogara negli Stati Uniti (novembre 1937)',

in Storia Contemporanea, 23 (1g82), pp. 32 1-8,

![]() [1] Bernardino Nogara (Bellano, June 17, 1870 — Milano, November 15, 1958)

[1] Bernardino Nogara (Bellano, June 17, 1870 — Milano, November 15, 1958)

(Pictured )The Eastern Trading Company in the Galata neighborhood of Constantinople around 1910 (Nogara Family Archive)

He was the first non-roman to be in charge of the Vatican finances. He came from a family so Catholic that it weep because of the breach of Porta Pia. With a degree in industrial and electro-technical engineering from the University of Milan, he left for England as soon as he married and went to work in a mine in Wales. From there he was sent to a mine in Greece. In 1908, he was living in Constantinople and managing mines in Asia Minor. There, he founded the Eastern Commercial Society, a branch of the Banca Commerciale Italiana. Well-versed in the political and economic realities of the Ottoman Empire, he became the Italian government’s trusted advisor for Easter affairs. In this role, he was involved in the Ouchy Treaty, which ended the war in Libya between Italy and Turkey. In 1914, Nogara was the Italian delegate to the Board of Administration for the Ottoman Public Debt. At the end of the First World War, he was part of the economic and financial commission of the Conferences created to draft peace treaties with Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

Bernardino Nogara was the financial advisor to the Vatican between 1929 and 1954, appointed by Pope Pius XI and retained by Pope Pius XII as the first Director of the Special Administration of the Holy See.

Volpi Connection

Giuseppe Volpi, 1st Count of Misurata (born in Venice on 19 November 1877; died in Rome on 16 November 1947), was an Italian businessman and politician.

Intesa Sanpaolo Group Historical Archives via Morone 3 (reading room) largo Mattioli 5 (postal address) 20121 Milan tel. +39 02 87942970 archivio.storico@intesasanpaolo.com

Bernardino Nogara

with his wife and children in Constantinople, 1910 (Nogara Family Archive)

The Galata Bridge in Constantinople; photo taken between 1908 and 1914

(Nogara Family Archive)

NO. 1 SEPTEMBER 2016 page 5

Europe’s great tragedy seen through a man’s letters to his wife Francesca Pino

She and their children had returned to Italy alone following a nearly decade-long stay in Istanbul, where Nogara worked for Banca Commerciale Italiana (BCI) as director of the Eastern Trading Company (Società Commerciale d’Oriente – COMOR); they ended up staying there due to the outbreak of WWI. The letters span a period of just over a year, from 2 July 1914 through 11 July 1915, just prior to Italy’s declaration of war on Turkey in August 2015. The book contains a single letter by Ester – the only one that has survived – dated 23 May 1915, the day that news got around of Italy’s entry into the war. It is found in the appendix for this reason. Bernardino Nogara[1] was a prominent figure in twentieth-century history. A liberal Catholic from an ancient Lombard family, he held a degree in mining engineering from the Milan Polytechnic and acted as BCI’s representative in the Mediterranean and Eastern European regions. A financier, he was also tasked with diplomatic responsibilities, and following the 1929 Concordat between the Vatican and Italy he became the first Director of the Special Administration of the Holy See. He was also a member of BCI’s board of directors from 1925 to 1945 when, thanks to his active participation in the National Liberation Committee in Rome, he was appointed the bank’s vice president on 28 June. He held that position until his death in 1958.

The correspondence is intriguing from several perspectives. First of all, it lets readers reconstruct the sequence of declarations of war between the various countries, which were bilateral and staggered over time. It also provides an understanding of the ambiguous behavior towards Russia of the Turks, who sided with Germany early on, allowing two German submarines to enter the Bosphorus. Bernardino Nogara’s reading of events is both diplomatic and highly perceptive, capturing the atmosphere of mistrust that developed within the international community following the entry into war of various countries. He had decided to stay on in Istanbul since a minimum number of board members was required to manage the administration of the Ottoman public debt. The letters show how Nogara grew increasingly convinced as time went by of the need for Italy to enter the war and subsequently to be able to claim the unredeemed lands (Trento and Trieste). He makes observations on the behavior of foreign ambassadors and Turkish ministers to his wife, who was herself quite familiar with that milieu; indeed, she had played a representative role that was very much appreciated by Italy’s ambassador in Constantinople, Camillo Garroni. Nogara’s comments convey the increasingly heavy atmosphere in the city, and the sense of isolation felt by the few Europeans still resident there.

At one point Nogara undertook a several day-long journey by ship and on horseback to visit the Heraclea mines in Anatolia, and then returned to Italy through Sofia and Thessaloniki, having obtained permission to visit his family in Bellano on Lake Como. Once in Italy he was called back repeatedly to carry out a range of diplomatic missions and assignments both for the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and for BCI and Otto Joel, the bank’s co-founder and director. Nogara’s writing style is eloquent yet terse, circumspect rather than rhetorical; indeed, his letters were often opened for censure. They include fascinating discussions of the growing difficulties of the postal and telegraph links, but also touch on more intimate, family-related matters such as the couple’s home, their garden, the care of plants and Nogara’s love for his wife. The elegant layout of the book and its exceptional selection of photographs (thanks to the analytical cataloguing done by Serena Berno, an Intesa Sanpaolo Group Historical Archives staff member) help readers to fully immerse themselves in the events of the period.

Published with the support of Intesa Sanpaolo, the book includes an introduction by Marta Petricioli on Italy’s foreign policy in the Mediterranean region, and on the role played by the aforementioned Società Commerciale d’Oriente, which also carried out banking business in Istanbul and other Mediterranean cities.

Lettere da Costantinopoli (1914-1915). Carteggio familiare di Bernardino Nogara [Letters from Constantinople (1914-1915). The Family Correspondence of Bernardino Nogara], edited by Bernardino Osio with an introduction by Marta Petricioli, Florence, Centro Di, 2014 (174 pages).

All credit for this elegant and absorbing volume – Lettere da Costantinopoli (1914- 1915). Carteggio familiare di Bernardino Nogara – is due to Bernardino Osio, a former ambassador, who conceived and edited it. It contains a brief part of the substantial correspondence between his grandfather, Bernardino Nogara, and Nogara’s wife, Ester Martelli.

Ambassador Bernardino Osio, grandson of Nogara, has his diary at his family archive in Rome. The diary has not so far been published, but has been used in two previous scholarly works: Renzo De Felice used extracts from the diary in his article, 'La Santa Sede e il conflitto italo-etiopico nel diario di Bernardino Nogara', Storia Contemporanea, 4 (1977), pp 823-34, and

Giovanni Belardelli published an important, attached document, the journal of Nogara's visit to the United States in 1937,'Un viaggio di Bernardino Nogara negli Stati Uniti (novembre 1937)',

in Storia Contemporanea, 23 (1g82), pp. 32 1-8,

[1] Bernardino Nogara (Bellano, June 17, 1870 — Milano, November 15, 1958)

[1] Bernardino Nogara (Bellano, June 17, 1870 — Milano, November 15, 1958) (Pictured )The Eastern Trading Company in the Galata neighborhood of Constantinople around 1910 (Nogara Family Archive)

He was the first non-roman to be in charge of the Vatican finances. He came from a family so Catholic that it weep because of the breach of Porta Pia. With a degree in industrial and electro-technical engineering from the University of Milan, he left for England as soon as he married and went to work in a mine in Wales. From there he was sent to a mine in Greece. In 1908, he was living in Constantinople and managing mines in Asia Minor. There, he founded the Eastern Commercial Society, a branch of the Banca Commerciale Italiana. Well-versed in the political and economic realities of the Ottoman Empire, he became the Italian government’s trusted advisor for Easter affairs. In this role, he was involved in the Ouchy Treaty, which ended the war in Libya between Italy and Turkey. In 1914, Nogara was the Italian delegate to the Board of Administration for the Ottoman Public Debt. At the end of the First World War, he was part of the economic and financial commission of the Conferences created to draft peace treaties with Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey.

Transactions of the Institution of Mining Engineers, Volume 34

By Institution of Mining Engineers (Great Britain) 1908 - Mineral industries

While in Istambul, he was appointed representative to the Italian Banca Commerciale and then the Italian representative to an international committee overseeing the Ottoman empire's debt and the Italian delegation to the economic committee at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919, after which he remained on the permanent reparations committee.[9] He was later appointed to manage the industry section of the Inter-Allied Commission that enacted the Dawes Plan in Berlin.

Within the Banca Commerciale Italiana, Italy's largest private bank, he became a member of the board of directors and later the vice-president. He was also a member of the board of Commissioni Economiche e Finanziarie alle Conferenze (Comofin).

Nogara's dealings with the Vatican began in 1914, when he purchased a variety of bonds on behalf of Pope Benedict XV.

He graduated in industrial engineering and electrical engineering at the Polytechnic of Milan in 1894, Nogales was later director of mines in England, Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey. In 1913 he was one of the architects of the signing of the Treaty of Ouchy concluded that the Libyan war between Italy and Turkey. It was also the Italian delegate, from the end of 1912, the Board of Directors of the Ottoman Public Debt, an adviser and then chief executive officer (1913-1935) of the Trading Company of the East (Comor), a sort of branch of the BCI in Turkey and the Balkans, director and vice president of BCI from 1925 to 1958.

Nogara could count on the benefits of a renewed diplomatic activity of the Church. Benedict XV had left the Vatican coffers empty, because the First World War prevented bishops from coming to Rome for ad limina visits and contribute to Peter’s Pence. From 1930 on, Nogara invested in a web of projects extended throughout Europe and financial centres in the United States and South America.

Giuseppe Volpi, 1st Count of Misurata (born in Venice on 19 November 1877; died in Rome on 16 November 1947), was an Italian businessman and politician.

Count Volpi developed utilities which brought electricity to Venice, northeast Italy, and the Balkans by 1903. In 1911-1912, he acted as a negotiator in ending the Italo-Turkish War. Treaty of Lausanne (1912) as Mr. Giuseppe Volpi, Commandant of the Orders of St. Maurice and St. Lazare and of the Italian Crown.

He was Mussolini’s governor of the colony of Tripolitania from 1921 to until 1925.

As Italy's Finance Minister from 1925 until 1928, he successfully negotiated Italy's World War I debt repayment with the United States and with England, and pegged the value of the lira to the value of gold. He was replaced in July 1928 by Antonio Moscini. He also founded the Venice Film Festival. The Volpi Cup (Italian: Coppa Volpi) is the principal award given to actors at the Venice Film Festival.

His son is automobile racing manager Giovanni Volpi.

.

President 1934–1943 of Confindustria (the Italian employers' federation, founded in 1910 ) after Alberto Pirelli (1934)

Giuseppe Volpi’s manager in Istanbul was Bernardino Nogara (Bellano, June 17, 1870 — Milano, November 15, 1958) a convert to Catholicism, a Sabbatean [*] Jew.

[*] Sabbateans (Sabbatians) is a complex general term that refers to a variety of followers of, disciples and believers in Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676), a Jewish rabbi who was proclaimed to be the Jewish Messiah in 1665 by Nathan of Gaza. Vast numbers of Jews in the Jewish diaspora accepted his claims, even after he became a Jewish apostate with his conversion to Islam in 1666. Sabbatai Zevi's followers, both during his "Messiahship" and after his conversion to Islam, are known as Sabbateans. They can be grouped into three: "Maaminim" (believers), "Haberim" (associates), and "Ba'ale Milhamah" (warriors).

↧

↧

UPDATE | Turkey - Credit Rating by Rats!

Turkey’s economy is doing surprisingly well. In the third quarter of 2017 GDP surged by 11.1% year-on-year, outperforming all major countries. Yet the outlook is not entirely rosy. Turkey’s current-account deficit has swelled from $33.7bn at the end of 2016 to $41.9bn (4.7% of GDP) now. Foreign direct investment is roughly half what it was a decade ago. Stirred by the credit boom, the spectre of high inflation, which haunted Turkey from the 1970s until the early 2000s, has returned. Prices surged by 13% in the year to November, the highest rate in 14 years, and more than double the central bank’s target.

Mavi Boncuk |

Turkey - Credit Rating

S&P Global Ratings unexpectedly lowered Turkey's sovereign credit rating to "BB-" from "BB" and revised its outlook to "stable" from "negative" on Tuesday 1st May 2018, citing growing concerns about inflation outlook and the long-term depreciation and volatility of Turkey's exchange rate, notwithstanding the central bank's recent decision to hike its late liquidity window rate. The agency also warned about the country's deteriorating external position; rising distress in the externally leveraged private sector and the Turkey's fiscal position due to continued public and quasi-public stimulus to the economy. Moody's credit rating for Turkey was last set at Ba2 with stable outlook. Fitch's credit rating for Turkey was last reported at BB+ with stable outlook. DBRS's credit rating for Turkey is BB (high) with negative outlook. In general, a credit rating is used by sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and other investors to gauge the credit worthiness of Turkey thus having a big impact on the country's borrowing costs. This page includes the government debt credit rating for Turkey as reported by major credit rating agencies.

S&P Global Ratings unexpectedly lowered Turkey's sovereign credit rating to "BB-" from "BB" and revised its outlook to "stable" from "negative" on Tuesday 1st May 2018, citing growing concerns about inflation outlook and the long-term depreciation and volatility of Turkey's exchange rate, notwithstanding the central bank's recent decision to hike its late liquidity window rate. The agency also warned about the country's deteriorating external position; rising distress in the externally leveraged private sector and the Turkey's fiscal position due to continued public and quasi-public stimulus to the economy. Moody's credit rating for Turkey was last set at Ba2 with stable outlook. Fitch's credit rating for Turkey was last reported at BB+ with stable outlook. DBRS's credit rating for Turkey is BB (high) with negative outlook. In general, a credit rating is used by sovereign wealth funds, pension funds and other investors to gauge the credit worthiness of Turkey thus having a big impact on the country's borrowing costs. This page includes the government debt credit rating for Turkey as reported by major credit rating agencies.Same old same old

AgencyRatingOutlookDate

S&PBB-stableMay 01 2018

Moody'sBa2stableMar 07 2018

Moody'sBaa3stableMay 05 1992

S&PBBBstableMay 04 1992

Turkey Economic Outlook

April 10, 2018

Concerns over an economic overheating are on the rise, with annual GDP growth coming in at a stronger-than-expected 7.3% increase in Q4, and inflation and external metrics quickly deteriorating. Investors’ appetite for risky emerging market assets—on which Turkey depends to finance its external deficits—has also moderated in recent weeks amid fears over a trade war between the U.S. and China, causing the lira to tumble to fresh all-time lows in early April. Nonetheless, authorities remain committed to injecting huge stimulus into the economy in an attempt to keep it humming ahead of general elections, currently set for November 2019 but with signs of a potential snap vote mounting. Against this backdrop, Moody’s downgraded the sovereign credit rating further into junk status in early March, arguing that the government’s focus on short-term measures undermined effective policymaking and economic reform.

Turkey Economic Growth

The economy is expected to decelerate from last year’s outstanding performance as credit stimulus ebbs and households take a breather following a debt-fueled spending spree last year. That said, the government’s singular focus on delivering strong headline growth ahead of general elections should see fiscal stimulus remaining vigorous this year. Geopolitical noise, widening current account deficits and sticky inflation, however, pose major downside risks to growth. Our panel expects growth of 4.1% this year, which is up 0.2 percentage points from last month’s estimate. It expects growth of 3.8% in 2019.

↧

Music | Professor John Morgan O'Connell

Commemorating Gallipoli through Music Remembering and Forgetting JOHN MORGAN O'CONNELL[1]

Commemorating Gallipoli through Music Remembering and Forgetting JOHN MORGAN O'CONNELL[1] This monograph examines the relationship between music and memory as it relates to the Gallipoli Campaign (1915-6). Drawing upon a wide variety of sources in many languages, it explores the multiple ways in which music is employed to remember and to forget, to celebrate and to commemorate a victory (on the part of the Central Powers) and a defeat (on the part of the Allied forces) in the Dardanelles during the First World War (1914-8). Further, it argues that commemoration itself can be viewed as an ‘instrument of war’. In particular, it investigates the complex positionality of individual actors during the centennial commemorations of the Gallipoli landings (24 April, 2015) where the Australians and the Turks most notably have employed music to reimagine the past, both nationalities invoking the ‘Gallipoli spirit’ (tr. ‘Çanakkale ruhu’) to advance a nationalist agenda and a resurgent militarism through the selective memorialization of an imperial past. The book interrogates through music the ambivalent position of minorities. With specific reference to the Irish (amongst the British) and the Armenians (amongst the Ottomans), it shows how song might serve both to articulate a nationalist defiance and an imperialist consensus during a tumultuous period of irredentism. By uncovering the complex pathways of musical transmission, it demonstrates through musical analysis how the colonized could become the colonizer (in the case of the Irish) or a minority might conform to a majority (in the case of the Armenians). Further, the publication looks at the uneasy alliance between the Turks and the Germans. It focuses on a German musician (as an imperial bandmaster) and Germanic entrepreneurs (in the recording industry) who entertained or who served the German Mission in Istanbul. Here, it considers by way of musical composition the shared wish on the part of the Germans and the Turks to create a Lebensraum in Asia.

Lexington Books Pages: 332 • Trim: 6 1/4 x 9 3/8 978-1-4985-5620-0 • Hardback • December 2017 978-1-4985-5621-7 • eBook • December 2017

Mavi Boncuk |

[1] Professor John Morgan O'Connell MA (Oxon), MA (UCLA), PhD (UCLA), AGSM

Professor

School of Music | oconnelljm(at)cardiff(dot)ac(dot) uk |+44 (0)29 2087 0394

Biography

I am an Irish ethnomusicologist with a specialist interest in cultural history. I have recently completed a monograph on music and commemoration as it relates to the Gallipoli Campaign from the perspective of the Australians and the Turks, the British and the Germans, amongst others (see O’Connell 2017). I also explore the issues of militarism and orientalism with respect to Irish recruits in the military catastrophe, my own family in particular having an ongoing connection with the Ottoman Empire. Some of my ancestors were administrators and soldiers in Ottoman territories, and others were diplomats and doctors in the Ottoman capital (see Figure 1). Significantly, a number of my relatives were either killed or wounded in the Gallipoli Campaign (see Figure 2).

This research builds upon my established interest in the music of the Middle East. It also draws upon my continued research on music in conflict zones. These academic strands have resulted in significant outputs in the form of a monograph (see O’Connell 2013) and a collection (see O’Connell Ed. 2010) respectively. I am currently working on a project that concerns music in Ireland during the Great War. I also aim to complete a study on music in the late Ottoman Empire. In addition, I have conducted impact related research in the Muslim world in association with the Aga Khan Humanities Project (see O’Connell 2015) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (2014).

My research concerns the musical traditions of the Muslim world, with a secondary area of expertise in the musical traditions of Europe. Other areas of interest include the significance of hermeneutic theory and historical ethnography for ethnomusicology. In 2013, I published a monograph on Turkish style in the early-Republican period (1923-1938). In 2010, I edited a scholarly collection that concerns music and conflict in a global perspective. Further, I have recently published chapters on music and humanism, music and classicism, and music and architecture. Having submitted for publication my latest book on music and commemoration in the Gallipoli Campaign (contract signed November, 2016), I am now undertaking a study of music in Ireland during the Great War.

I have acted as a music consultant for a number of international organizations, being awarded a Senior Fulbright Fellowship in association with the Aga Khan Humanities Project (2002) and a Getty Foundation Grant to participate in its International Summer Institute (2006). I was also awarded an AHRC fellowship (2014) for a project entitled ‘The God Article’. I have hosted a variety of international conferences including the 15th ICTM International Colloquium (2004) and the annual conference of the British Forum for Ethnomusicology (2008). I was reviews editor for the journal Ethnomusicology. I am currently a member of the editorial boards for the SOAS Musicology Series, Ethnomusicology Forum and the Journal of the Ottoman and Turkish Studies Association, amongst others.

Forthcoming Publications: Selected

O'Connell, John M. 2017. Commemorating Gallipoli: Music, Memory, Myth. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. [Accepted: 130,000 words]

O'Connell, John M. 2017. ‘Kâr-ı Nev: Elaboration and Retardation in the Musical Performances of a Turkish Classic’. Eds Rachel Harris and Martin Stokes. Theory and Practice in the Music of the Islamic World: Essays in Honour of Owen Wright. London: Routledge, 123-143. [Accepted: 10,000 words]

Education:

1996: PhD (Ethnomusicology) UCLA, USA

1992: MA (Music) UCLA, USA

1986: AGSM (Performance) Guildhall School of Music, UK

1985: MA (Geography) Oxford University, UK

1982: BA (Geography) Oxford University, UK

Fellowships: Selected

2006: Getty Foundation Internship, Koç Üniversitesi, Turkey

2002: Fulbright Senior Scholar Award, Brown University, USA

2001: Music Consultant, Aga Khan Humanities Project, Tajikistan

1992: Turkish Government Fellowship, İstanbul Üniversitesi, Turkey

1991: Graduate Distinguished Scholar, UCLA, USA

1990: DAAD Fellowship, Freie Universität, Germany

1988: Graduate Fellowship, UCLA, USA

1987: Research Associate, York University, UK

Academic positions

Permanent Appointments:

Otago University (Lecturer)

University of Limerick (Senior Lecturer)

Cardiff University (Professor)

Visiting Appointments:

Queen's University (Visiting Lecturer)

Brown University (Visiting Professor)

Haverford College (Distinguished Visiting Professor), among others

Speaking engagements

Recent: Selected (2014-)

2017: ‘Old Gallipoli: Music in the Commemoration of a Campaign', CoHere Symposium, Newcastle University, Newcastle (UK)

2017: 'Bedî Mensî: Hüseyin Sadettin ve Türk Operası', Hüseyin Sadettin Arel Sempozyomu, İstanbul Üniversitesi, Istanbul (Turkey)

2017: ‘De la musique pour la guerre: pluralisme et chauvinisme’, La Fondation Royaumont, Paris (France)

2017: Keynote. ‘Heal the Pain: The Arts in the Dardanelles (1915)’, Centre for Nineteenth Century Studies, Durham University (UK)

2016: ‘Turân: A Turkic Myth in Turkish Music’, Middle East and Central Asia Music Forum, SOAS, London (UK)

2016: ‘Telling Tales: Musical Creativity and National Identity in the Gallipoli Campaign’, Commemorating WWI, National Museum, Cardiff (UK)

2016: ‘Saz as Symbol: A Turkic Lute in the Turkish Diaspora’, Music of the Silk Road, Shanghai Conservatory, Shanghai (China)

2015: ‘The Classical Style: Modal Analysis of a Vocal Improvisation in Turkey’, 3rd International Mugam Symposium, Baku (Azerbaijan)

2015: ‘The Pulse of Asia: Musical Diffusion and Environmental Determinism in Central Asia’, International Council for Traditional Music, Astana (Kazakhstan)

2014: ‘Usûlsüz: A Matter of Meter in the Concerts of Münir Nurettin Selçuk (1923-1938)’, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität, Münster (Germany)

2014: ‘Ottomanism Revived: Jewish Musicians and Cultural Politics in Turkey’, Society for Ethnomusicology, Pittsburgh (USA)

2014: ‘Concert Platform: Style and Space in Turkish Music’, Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisation, London (UK)

2014: ‘Mythality: Myth and Reality in Turkish Music’, Arnolfini, Bristol (UK)

Articles

O'Connell, J. M. 2015. Iranian classical music: the discourse and practice of creativity. By Laudan Nooshin [Book Review]. Music and Letters 96(4), pp. 677-679. (10.1093/ml/gcv080)

O'Connell, J. M. 2011. Music in war, music for peace: A review article. Ethnomusicology 55(1), pp. 112-127. (10.5406/ethnomusicology.55.1.0112)

O'Connell, J. M. 2010. A staged fright: Musical hybridity and religious intolerance in Turkey, 1923-38. twentieth-century music 7(1), pp. 3-28. (10.1017/S147857221100003X) pdf

O'Connell, J. M. 2010. Music and the play of power in the Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia. Laudan Nooshin, ed. [Book Review]. Ethnomusicology 54(2), pp. 347-351. (10.5406/ethnomusicology.54.2.0347)

O'Connell, J. M. 2007. Timothy D. Taylor, Beyond exoticism: Western music and the world (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), ISBN 978 0 8223 9571 (hb), 978 0 8223 3968 7 (pb) [Book Review]. Twentieth-Century Music 4(2), pp. 261-265. (10.1017/S1478572208000546)

O'Connell, J. M. 2007. Falak: the voice of destiny: traditional, popular and symphonic music of Tajikistan. Compiled by Federico Spinetti [Musical Recording Review]. Ethnomusicology Forum 16(1), pp. 179-181. (10.1080/17411910701273101)

O'Connell, J. M. 2006. National symposium: towards a national ethnomusicology. Bulletin of the International Council for Traditional Music 109, pp. 61-62.

O'Connell, J. M. 2005. The Edvâr of Demetrius Cantemir: recent publications. Ethnomusicology Forum 14(2), pp. 235-239. (10.1080/17411910500415887)

O'Connell, J. M. 2005. In the time of Alaturka: Identifying difference in musical discourse. Ethnomusicology 49(2), pp. 177-205.

O'Connell, J. M. 2005. The 15th ICTM colloquium: identifying conflict in music, resolving conflict through music. Bulletin of the International Council for Traditional Music 106, pp. 55-57.

O'Connell, J. M. and Smith, T. 2005. Liaison officer report: Ireland. Bulletin of the International Council for Traditional Music 106, pp. 65-67.

O'Connell, J. M. 2004. Liaison officer report: Ireland. Bulletin of the International Council for Traditional Music 105, pp. 24-27.

O'Connell, J. M. 2004. The tale of Crazy Harman: the musician and the concept of music in the Türkmen epic tale, Harman Däli by Sławomira Żerańska-Kominek [Book Review]. Yearbook for Traditional Music 36, pp. 171-175.

O'Connell, J. M. 2003. A resounding issue: Greek recordings of Turkish music, 1923-1938. Middle East Studies Association Bulletin 37(2), pp. 200-216.

O'Connell, J. M. 2003. Song cycle: the life and death of the Turkish gazel: a review essay [Musical Recordings Review]. Ethnomusicology 47(3), pp. 399-414. (10.2307/3113948)

O'Connell, J. M. 2003. Music of the Ottoman court: makam, composition and the early Ottoman instrumental repertoire by Walter Feldman [Book Review]. Edebiyât 13(2), pp. 260-263. (10.1080/0364650032000143283)

O'Connell, J. M. 2001. Fine art, fine music: Controlling Turkish taste at the Fine Arts Academy in 1926. Yearbook for Traditional Music 32, pp. 117-142. (10.2307/3185245)

O'Connell, J. M. 1991. Die musik der Araber (The music of the Arabs) by Habib Hasan Touma [Book Review]. Asian Music 22(1), pp. 154-156. (10.2307/834296)

O'Connell, J. M. 1989. Jean During. La musique traditionnelle de I'Azerbayjan et la science des muqâms [Book Review]. Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology 5, pp. 130-132.

Books

O'Connell, J. 2017. Commemorating Gallipoli through music: Remembering and forgetting. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, Lexington Monographs.

O'Connell, J. M. 2013. Alaturka: Style in Turkish music (1923-1938). SOAS Musicology Series. Aldershot: Ashgate.

O'Connell, J. M. and El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, S. eds. 2010. Music and Conflict. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Book Sections

O'Connell, J. M. 2017. Usûlsüz: Meter in the Concerts of Münir Nurettin Selçuk (1923-1938). In: Jäger, R. M., Helvacı, Z. and Olley, J. eds. Rhythmic cycles and structures in the art music of the Middle East. Ergon Verlag, pp. 247-276.

O'Connell, J. M. 2017. Concert platform: a space for a style in Turkish music. In: Spinetti, F. and Frishkopf, M. eds. Music, Sound, and Architecture in Islam. University of Texas Press, pp. 79-109.

O'Connell, J. 2017. Kâr-ı Nev: elaboration and retardation in the musical performances of a Turkish classic. In: Harris, R. and Stokes, M. eds. Theory and Practice in the Music of the Islamic World: Essays in Honour of Owen Wright. Routledge, pp. 123-143.

O'Connell, J. M. 2015. Gazel. In: Jankowsky, R. C. ed. Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Vol. 10.Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World Bloomsbury Academic, pp. 35-37.

O'Connell, J. M. 2015. Modal trails, model trials: Musical migrants and mystical critics in Turkey. In: Davis, R. ed. Musical Exodus: Al-Andalus and its Jewish Diasporas. Europea: Ethnomusicologies and Modernities Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, pp. 101-124.

O'Connell, J. M. 2015. Music and humanism in the Aga Khan Humanities Project. In: Pettan, S. and Titon, J. T. eds. The Oxford Handbook of Applied Ethnomusicology. Oxford Handbooks Oxford University Press, pp. 602-638.

O'Connell, J. M. 2015. The classical style: modal analysis of vocal improvisation in Turkey. In: Agayeva, S. ed. Space of Maugham. Şerq-Qerb, pp. 124-139.

O'Connell, J. M. 2013. Pir Sultan Abdal. In: Fleet, K. et al. eds. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill, pp. 135-136 ,(10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23910)

O'Connell, J. M. 2013. Beste. In: Fleet, K. et al. eds. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill, pp. 52-53 ,(10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24017)

O'Connell, J. M. 2010. Alabanda: Brass bands and musical methods in Turkey. In: Spinetti, F. ed. Giuseppe Donizetti Pasha: Musical and Historical Trajectories between Italy and Turkey [Giuseppe Donizetti Pascià: Traiettorie Musicali e Storiche tra Italia e Turchia]. Saggi e Monografie, Vol. 7. Bergamo, Italy: Fondazione Donizetti, pp. 19-37.

O'Connell, J. M. 2010. Music in war. In: O'Connell, J. M. and El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, S. eds. Music and Conflict. University of Illinois Press, pp. 15-16.

O'Connell, J. M. 2010. Introduction: an ethnomusicological approach to music and conflict. In: O'Connell, J. M. and El-Shawan Castelo-Branco, S. eds. Music and Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, pp. 1-14.

O'Connell, J. M. 2009. Ayin. In: Fleet, K. et al. eds. Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill, pp. 86-87 ,(10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23036)

O'Connell, J. M. 2008. War of the Waves: Cypriot Broadcasting in Great Britain. In: Hemetek, U. and Sağlam, H. eds. Music from Turkey in the Diaspora. Klanglese, Vol. 5. Vienna: Institut für Volksmusikforschung und Ethnomusikologie, pp. 119-130.

O'Connell, J. M. 2006. 'The mermaid of the Meyhane: the legend of a Greek singer in a Turkish tavern'. In: Linda, P. A. and Inna, N. eds. Music of the Sirens. Indiana University Press, pp. 273-293.

O'Connell, J. M. 2005. 'Sound sense: mediterranean music from a Turkish perspective'. In: Cooper, D. and Dawe, K. eds. The Mediterranean in Music. Scarecrow Press, pp. 3-25.

O'Connell, J. M. 2004. Sustaining difference: theorizing minority musics in Badakhshan. In: Hemetek, U. et al. eds. Manifold Identites. Cambridge Scholars Press, pp. 1-19.

O'Connell, J. M. 2002. From Empire to Republic: vocal style in twentieth century Turkey. In: Danielson, V., Marcus, S. and Reynolds, D. eds. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East, Vol. 6. Routledge, pp. 781-787.

O'Connell, J. M. 2002. Snapshot: Tanburî Cemil Bey. In: Danielson, V., Marcus, S. and Reynolds, D. eds. The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music: The Middle East. Routledge, pp. 757-758.

O'Connell, J. M. 2001. Major minorities: towards an ethnomusicology of Irish minority musics. In: Pettan, S., Reyes, A. and Komavec, M. eds. Music and Minorities. ZRC Publishing, pp. 165-182.

O'Connell, J. M. 2001. Münir Nurettin Selçuk. In: Sadie, S. and Tyrrell, J. eds. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press, pp. 55-56.

O'Connell, J. M. 1998. The Arab in Arabesk: style and stereotype in Turkish vocal performance. In: Wharton, B. and Adawy, N. eds. The Limerick Anthology of Arab Affairs. University of Limerick Press, pp. 87-103.

↧

London’s East End Film Win for "Daha" | Karlovy Vary Reviews

Mavi Boncuk |

Variety Review

Karlovy Vary Review: ‘More’

A young man is corrupted by his father's human trafficking business in Turkish actor Onur Saylak's gripping, grueling directorial debut.

By Jessica Kiang

With: Hayat Van Eck, Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan, Turgut Tunçalp, Tankut Yıldız, Tuba Büyüküstün (Turkish, Arabic dialogue)

The blue Aegean sparkles under blazingly sunny skies. The view from a promontory is of rocky cliffs rising from a curving, fertile, beach-fringed bay, and of a series of crags jutting up out of the water like stepping stones to a hopeful horizon. It’s a picture that’s nobody’s idea of Hell, but all Hell needs is a devil in residence, and this strip of the Turkish coast has one, plus another in waiting. Popular Turkish actor Onur Saylak makes an audacious, provocative directorial debut with his adaptation of Hakan Günday’s novel, a film that impresses for its craftsmanship and performances almost as much as it depresses with its relentless, uncompromising depiction of humanity’s basest depravities. Presenting the refugee emergency from a viewpoint rarely explored — that of the traffickers who exploit it for monetary gain — “More” adds a dimension of horror to the humanitarian catastrophe, and convincingly suggests it’s a crisis that corrupts everyone and everything it touches.

Gaza (Hayat Van Eck) is a bright young man who has never left the small Turkish seaside town of his birth — and why would he, given that, as he intones in one of the film’s confessional voiceovers, he is “the son of the most important man alive.” His father, Ahad (Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan), hardly looks the part: balding, boorish, jowly and rotund. But Ahad’s real business is not the fruit and vegetable delivery service indicated on his van; it’s the lucrative job of collecting and hiding batches of 20 or 30 people at a time as they flee, mostly from Syria, before some equally unscrupulous boatsmen smuggle them away again across that treacherously calm-looking azure sea.

Ahad has a cellar built specially for this purpose and it’s Gaza’s job to maintain it, to provide the refugees with the basic necessities of food and water while Ahad feels little compunction in exercising his Godlike powers over them, extorting further cash bribes from the men and raping the women or pimping them out to local bigwigs. And so this is a pivotal moment for Gaza, who has a decision to make about who he is, with his own innocence and decency little more than a guttering candle in the darkness of his vicious and venal father’s example. The already grim proceedings take an even grimmer turn following the death of a little boy and the subsequent murder of his mother, and the point of no return arrives quickly.

Saylak has cast his film with care, and gets exceptionally committed performances from Taylan and, in particular, from Van Eck. The sullen Gaza seems to almost physically change over the course of the film, from baby-faced boyishness to a sunken brutishness, his eyes set deep beneath a heavy forehead. In certain light, he can look positively demonic — indeed Feza Çaldiran’s stark, rich photography makes painterly use of directional light throughout, with slices of illumination slanting through otherwise inky frames. Even the sun-drenched exteriors start to feel claustrophobic as the promise of that far-off horizon turns into a taunt.

By contrast, a few of the more literary conceits don’t quite work in translation from page to screen, such as the odd occasional inter-title counting down of days, or the sporadic voiceover that ultimately acts as a red herring concerning the film’s intentions for Gaza. And there’s a sense that in following the novel all the way down to its most hellish extreme and lingering there, the film might actually somewhat dull the message: Its villains become so devoid of humanity they’re somehow easier to dismiss as monsters. Less might have benefited “More,” which is already a difficult, despairing watch, but the ferocity of its intent is both justified and admirable.

It’s ironic that the term for moving undocumented refugees is known as “human trafficking” when its inevitable effect is the dehumanization of its victims. And the central theme of “More” is how that process happens in parallel: the less Gaza sees these people as people, the less of a person he becomes. From there it’s no big leap to understand the film’s most sobering message — one that sits sickly in the pit of your stomach for some time after the movie ends: The lost souls searching for a better life over that duplicitous horizon are far from the only souls lost to this crisis.

Karlovy Vary Review: 'More'

Reviewed at Karlovy Vary Film Festival (competing), July 3, 2017. Running time: 117 MIN. (Original Title: "Daha")

PRODUCTION: (Turkey) An Ay Yapim production, in co-production with b.i.t arts. (International sales: Heretic Outreach, Athens.) Producers: Kerem Çatay. Executive Producer: Yamac Okur.

CREW: Director: Onur Saylak. Screenplay: Saylak, Hakan Günday, Doğu Yaşar Akal, based on the novel "Daha" by Hakan Günday. Camera (color): Feza Çaldiran. Editor: All Aga. Music: Uygur Yigit.

WITH: Hayat Van Eck, Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan, Turgut Tunçalp, Tankut Yıldız, Tuba Büyüküstün (Turkish, Arabic dialogue)

'More' ('Daha'): Film Review | Karlovy Vary 2017 by Boyd van Hoeij

An impressively controlled and complex debut. TWITTER

Turkish actor Onur Saylak ('Autumn') casts young Hayat Van Eck opposite veteran Ahmet Mumtaz Taylan ('Once Upon a Time in Anatolia') in his impressive directorial debut.

A film about a 14-year-old boy helping out his father at work in a rural outpost on the sea would probably feature gorgeous landscapes but wouldn’t necessarily make for an interesting story. But Gaza, the protagonist of the hard-hitting Turkish drama More (Daha), isn’t just any teen, and his father, involved in smuggling people from the war-torn Middle East into nearby Greece, doesn’t just have any old job. Turkish actor Onur Saylak (Autumn) makes an auspicious debut as a director here, turning Hakan Gunday’s ink-black novel of despair into a film that’s a hard sit but that suggests an awful lot — awful being the operative word — about the world we live in today.

After its world premiere in competition at the recent Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, this should travel far and wide and drum up significant interest for whatever Saylak decides to do next as a director.

Ahad (Ahmet Mumtaz Taylan) is a heavy-set man with an equally heavy brow who exploits opportunities wherever he sees them and who expects unquestioned loyalty from the handful of people he works with, including his most loyal aid, Gaza (Hayat Van Eck), his teenage boy. The adolescent, with vivid and alert eyes and a can-do attitude that is probably more rooted in his relative innocence than in his character, is curious about the world and a good student. He’s been secretly testing for a good school in faraway Istanbul, though Dad isn’t very interested in his academic results, telling him to “f— school,” and that’s hardly the first sign he’s not an ideal parent.

Ahad — which, when read backwards, spells Daha, the film’s Turkish title — owns a small truck that he nominally transports fruit and vegetables with along the coast. But the vehicle is also used to take especially Syrian refugees from a nearby marsh to the large but dark basement underneath Ahad’s garage and from there, when the weather allows it, onto a boat that will take them to nearby Greece. Refugees generally seem to stay a couple of days in transit in the underground store room, during which Gaza is charged with making them food and distributing water bottles.

The task isn’t an easy one, but initially Gaza seems to tackle it like any complex challenge at school. There are cultural and language barriers — Syrians don’t speak Turkish and Turks don’t speak Arabic — but the boy manages to do a good job and even tries to improve the refugees’ living standards somewhat by reorganizing the cellar. Whether to show his appreciation or to try and convince him to stay at home rather than leave him behind and move to the big city, Ahad allows Gaza to smoke and drink and feel like he’s an adult. He even offers him to become a partner, rather than an apprentice, in his booming refugee business.

Neither of the men is a big talker, so Saylak, who co-penned the adaptation with Dogu Yasar Akal and Gunday, has to use other means to communicate what the men are thinking and how their characters are evolving. One of the main conduits of information is their physical reaction to some extreme occurrences, starting with one of the film’s most intense sequences, in which Dad drags a female refugee from the basement into their home one night to rape her. This has happened before and is amply foreshadowed, so it is not much of a surprise when it occurs. What does surprise is the way in which Saylak stages the rape, suggesting its extremely violent impact on both the poor refugee and the perpetrator’s son while keeping the actual rape entirely offscreen.

As the woman tries to escape the horror, Ahad finally manages to catch her and he brutalizes her in the corridor while director of photography Feza Caldiran stays in Gaza’s tiny bedroom. As if to literally block out what’s happening, the upset teen has closed his bedroom door and has sat down against it, with first the woman banging on the door for help and then a horrific pounding heard as Ahad has his way with her right behind the door. Gaza, who is the only one in the frame, can’t help but put his hands over his ears, a gesture that at once suggests how aggressive the assault is — the soundwork is appropriately terrifying — but which simultaneously reduces Gaza to something of a child, as he knows what’s happening but won’t do anything about it but pretend he can’t hear it.

There are more scenes that rely on other things than dialogue for their very visceral impact, though Saylak doesn’t always know how to exploit them for maximum impact. A rap song that Gaza has heard from some local boys, for example, seems to toughen his resolve and at one point serves as a way to prep him for a possible confrontation with his father. But the sequence — one of many that showcase the impressive and raw talents of Van Eyck — is all setup and no payoff, as Gaza, chanting the song’s chorus and mock-fighting, works up the courage to see eye-to-eye with his brute of a father. Ahad then arrives to confront his son, but Saylak suddenly skips ahead to the next, seemingly unrelated scene.

There are a few other small missteps like this, as well as some elements that are unnecessary. They include a sporadic voiceover from the older (but never seen) Gaza that reeks of literary pretension and actually distances the viewer more from the 14-year-old’s point-of-view rather than bringing him closer and a couple of very specific time-jumps — “78 days more” — that not only sound awkward in English (perhaps the nod to the title makes more sense in Turkish?) but don’t really add anything. Even so (spoiler ahead), More remains a tautly structured, carefully crescendoing story of a young boy full of promise whose potential and innate goodness are slowly being ground to a pulp by those around him who, and this is the real tragedy, in turn once probably were bright young things themselves. The bitter irony of becoming a heartless human while handling refugees that are escaping worse situations on their way to what they hope will be a better life makes More not only hard to watch but also announces Saylak as a very gifted storyteller who can handle complex material with impressive directorial confidence.

For the record, the film received no state funding from Turkey and was made only with private backing.

Production companies: Ay Yapim, Bit Arts

Cast: Hayat Van Eck, Ahmet Mumtaz Taylan, Turgut Tuncalp, Tankut Yildiz, Tuba Buyukustun

Director: Onur Saylak

Screenplay: Hakan Gunday, Onur Saylak, Dogu Yasar Akal, based on the novel by Hakan Gunday

Producer: Kerem Catay

Director of photography: Feza Caldiran

Production designers: Dilek Ayaztuna, Aykut Ayaztuna

Editor: Ali Aga

Music: Uygur Yigit

Venue: Karlovy Vary International Film Festival

Sales: Heretic Outreach

In Turkish, Arabic

115 minutes

London’s East End Film Festival has unveiled the winners from its 17th edition, with Turkish drama Daha taking home best film.

The directorial debut of Turkish actor Onur Saylak (The Blue Wave), Daha follows an unhappy teenager in a coastal Turkish town whose life is corrupted by his father’s people-trafficking business. It is an adaptation of a novel by Hakan Günday.

The award was given by a jury comprised of radio and TV host Edith Bowman, producer Dominic Buchanan, actress Ophelia Lovibond, and screenwriter and critic Kate MuirBowman said of the winner, “Such a raw story – really stayed with me. Great performances and incredible first outing for Onur Saylak.”

The other jurors added that the film was “terrific”, “gripping” and “emotionally devastating”.

Variety Review

Karlovy Vary Review: ‘More’

A young man is corrupted by his father's human trafficking business in Turkish actor Onur Saylak's gripping, grueling directorial debut.

By Jessica Kiang

With: Hayat Van Eck, Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan, Turgut Tunçalp, Tankut Yıldız, Tuba Büyüküstün (Turkish, Arabic dialogue)

The blue Aegean sparkles under blazingly sunny skies. The view from a promontory is of rocky cliffs rising from a curving, fertile, beach-fringed bay, and of a series of crags jutting up out of the water like stepping stones to a hopeful horizon. It’s a picture that’s nobody’s idea of Hell, but all Hell needs is a devil in residence, and this strip of the Turkish coast has one, plus another in waiting. Popular Turkish actor Onur Saylak makes an audacious, provocative directorial debut with his adaptation of Hakan Günday’s novel, a film that impresses for its craftsmanship and performances almost as much as it depresses with its relentless, uncompromising depiction of humanity’s basest depravities. Presenting the refugee emergency from a viewpoint rarely explored — that of the traffickers who exploit it for monetary gain — “More” adds a dimension of horror to the humanitarian catastrophe, and convincingly suggests it’s a crisis that corrupts everyone and everything it touches.

Gaza (Hayat Van Eck) is a bright young man who has never left the small Turkish seaside town of his birth — and why would he, given that, as he intones in one of the film’s confessional voiceovers, he is “the son of the most important man alive.” His father, Ahad (Ahmet Mümtaz Taylan), hardly looks the part: balding, boorish, jowly and rotund. But Ahad’s real business is not the fruit and vegetable delivery service indicated on his van; it’s the lucrative job of collecting and hiding batches of 20 or 30 people at a time as they flee, mostly from Syria, before some equally unscrupulous boatsmen smuggle them away again across that treacherously calm-looking azure sea.

Ahad has a cellar built specially for this purpose and it’s Gaza’s job to maintain it, to provide the refugees with the basic necessities of food and water while Ahad feels little compunction in exercising his Godlike powers over them, extorting further cash bribes from the men and raping the women or pimping them out to local bigwigs. And so this is a pivotal moment for Gaza, who has a decision to make about who he is, with his own innocence and decency little more than a guttering candle in the darkness of his vicious and venal father’s example. The already grim proceedings take an even grimmer turn following the death of a little boy and the subsequent murder of his mother, and the point of no return arrives quickly.

Saylak has cast his film with care, and gets exceptionally committed performances from Taylan and, in particular, from Van Eck. The sullen Gaza seems to almost physically change over the course of the film, from baby-faced boyishness to a sunken brutishness, his eyes set deep beneath a heavy forehead. In certain light, he can look positively demonic — indeed Feza Çaldiran’s stark, rich photography makes painterly use of directional light throughout, with slices of illumination slanting through otherwise inky frames. Even the sun-drenched exteriors start to feel claustrophobic as the promise of that far-off horizon turns into a taunt.