The Morlach troops was an irregular military group in the Dalmatian hinterland, composed of "Morlachs", that was hired by the Republic of Venice to fight the Ottoman Empire during the Cretan War (1645–69) and the Great Turkish War (1683–99). The leaders, called harambaša (tr. "harami basi | bandit leader") and serdar ("commander-in-chief"), held several titles in Venetian service.

With the Cretan War (1645–69), a solid organization was needed, with an officer commanding over several harambaše. At first this position was undetermined. Priest Stjepan Sorić is mentioned as "governator delli Morlachi", Petar Smiljanić as "capo", Vuk Mandušić as "capo direttore", and Janko Mitrović as "capo principale de Morlachi", Jovan Dračevac as "governator" etc. This "Uskok" or "Morlach" army had less than 1,500 fighters.

Stanko Guldescu argued that the Vlachs or Morlachs, were Latin speaking and pastoral peoples who lived in the Balkan mountains since pre-Roman times Morlachs were Slavicized and partially Islamized during Turkish occupation. Silviu Dragomir wrote that the Vlachs were called Morlachs by Venetians and Velebit county was named Morlacca for a while and the naval channel in vicinity was called "canale della Morlacca" Cicerone Poghirc showed that Morlach is an Italian translation of the Turkish name Kara Vlah[1] | Caravlach. "Cara" means "Black" in Turkish but means North in Turkish geography. So Morlachs are Northern Vlachs in opposition with the Vlachs from Greece.

The word Morlach is derived from Italian Morlacco and Latin Morlachus or Murlachus, being cognate to Greek Μαυροβλάχοι Maurovlachoi, meaning "Black Vlachs" (from Greek μαύρο mauro meaning "dark", "black"). The Croatian and Serbian term in its singular form is Morlak; its plural form is Morlaci [mor-latsi]. In some 16th-century redactions of the Doclean Chronicle, they are referred to as "Morlachs or Nigri Latini" (Black Latins). Petar Skok suggested it derived from the Latin maurus and Greek maurós ("dark"), the diphthongs au and av indicating a Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant.

The word Morlach is derived from Italian Morlacco and Latin Morlachus or Murlachus, being cognate to Greek Μαυροβλάχοι Maurovlachoi, meaning "Black Vlachs" (from Greek μαύρο mauro meaning "dark", "black"). The Croatian and Serbian term in its singular form is Morlak; its plural form is Morlaci [mor-latsi]. In some 16th-century redactions of the Doclean Chronicle, they are referred to as "Morlachs or Nigri Latini" (Black Latins). Petar Skok suggested it derived from the Latin maurus and Greek maurós ("dark"), the diphthongs au and av indicating a Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant. Dimitrie Cantemir, in his History of the Growth and Decay of the Ottoman Empire remarks that when Moldavia was subdued to the Ottoman Rule by Bogdan III, Moldavia was referred to by the Ottomans as "Ak iflac", or Ak Vlach (i.e., White Wallachians), while the Wallachians were known as "Kara iflac", or Kara Vlach, (i.e., Black Wallachians). "Black Vlachs" can in fact mean "Northern Vlachs", because the Turkish word "kara" means black but also means North in old Turkish.

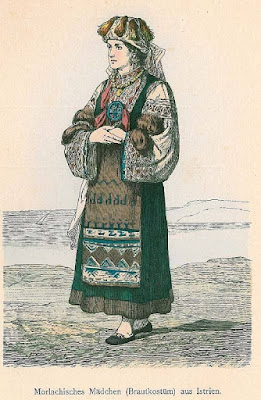

Dimitrie Cantemir, in his History of the Growth and Decay of the Ottoman Empire remarks that when Moldavia was subdued to the Ottoman Rule by Bogdan III, Moldavia was referred to by the Ottomans as "Ak iflac", or Ak Vlach (i.e., White Wallachians), while the Wallachians were known as "Kara iflac", or Kara Vlach, (i.e., Black Wallachians). "Black Vlachs" can in fact mean "Northern Vlachs", because the Turkish word "kara" means black but also means North in old Turkish. There are several interpretations of the ethnonym and phrase "moro/mavro/mauro vlasi". The direct translation of the name Morovlasi in Croatian and Serbian languages would mean Black Vlachs. It was considered that "black" referred to their clothes of brown cloth. The 17th-century Venetian Dalmatian historian Johannes Lucius suggested that it actually meant "Black Latins", compared to "White Romans" in coastal areas. The 18th-century writer Alberto Fortis in his book Travels in Dalmatia (1774), in which he wrote extensively about the Morlachs, thought that it derived from the Slavic more ("sea") – morski Vlasi meaning "Sea Vlachs". 18th-century writer Ivan Lovrić, observing Fortis' work, thought that it came from "more" (sea) and "(v)lac(s)i" (strong) ("strongmen by the sea"),[6] and mentioned how the Greeks called Upper Vlachia Maurovlachia and that the Morlachs would have brought that name with them.[7][8] Cicerone Poghirc and Ela Cosma offer a similar interpretation that it meant "Northern Latins", derived from the Indo-European practice of indicating cardinal directions by colors.

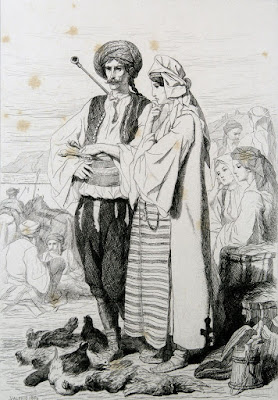

There are several interpretations of the ethnonym and phrase "moro/mavro/mauro vlasi". The direct translation of the name Morovlasi in Croatian and Serbian languages would mean Black Vlachs. It was considered that "black" referred to their clothes of brown cloth. The 17th-century Venetian Dalmatian historian Johannes Lucius suggested that it actually meant "Black Latins", compared to "White Romans" in coastal areas. The 18th-century writer Alberto Fortis in his book Travels in Dalmatia (1774), in which he wrote extensively about the Morlachs, thought that it derived from the Slavic more ("sea") – morski Vlasi meaning "Sea Vlachs". 18th-century writer Ivan Lovrić, observing Fortis' work, thought that it came from "more" (sea) and "(v)lac(s)i" (strong) ("strongmen by the sea"),[6] and mentioned how the Greeks called Upper Vlachia Maurovlachia and that the Morlachs would have brought that name with them.[7][8] Cicerone Poghirc and Ela Cosma offer a similar interpretation that it meant "Northern Latins", derived from the Indo-European practice of indicating cardinal directions by colors. From the 16th century onward, the historical term changes meaning, as in most Venetian documents, Morlachs are now usually called immigrants, both Orthodox and Catholic, from the Ottoman-conquered territories in the Western Balkans (chiefly Bosnia and Herzegovina). These settled in the Venetian-Ottoman frontier, in the hinterlands of coastal cities, and entered Venetian military service by the early 17th century.

[1 Vlachs (Latin: Valachi; Ottoman Turkish: Eflak, pl. Eflakân; Serbo-Croatian: Vlah/Влах, pl. Vlasi/Власи) was a social and fiscal class in several late medieval states of Southeastern Europe, and also a distinctive social and fiscal class within the millet system of the Ottoman Empire, composed largely of Eastern Orthodox Christians who practiced nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoral lifestyle, including populations in various migratory regions, mainly composed of ethnic Vlachs and Serbs. At that time the amalgamation of the process of sedentarization of the Orthodox Vlachs and their gradual fusion into the Serbian rural population reached a high level and was officially recognized by the Ottoman authorities.

“The Rüsûm-i Eflakiye was a tax on Vlachs in the Ottoman Empire. Vlachs in the Balkans were granted tax concessions under Byzantine and Serb rulers in return for military service; and this continued under Ottoman rule. Instead of some of the customary taxes, they paid a special "Vlach tax", Rüsûm-i Eflakiye: One sheep and one lamb from each household on St. Georges Day each year. Because Vlachs were taxed differently, they were listed differently in defters.”

Source: Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-0-8147-5561-7.

"In 1630 the Habsburg Emperor signed the Statuta Valachorum, or Vlach Statutes (Serbs and other Balkan Orthodox peoples were often called Vlachs). They recognized formally the growing practice of awarding such refugee families a free grant of crown land to farm communally as their zadruga. In return all male members over sixteen were obliged to do military service. The further guarantees of religious freedom and of no feudal obligations made the Orthodox Serbs valuable allies for the monarchy in its seventeenth-century struggle ..."

Source: John R. Lampe; Marvin R. Jackson (1982). Balkan Economic History, 1550-1950: From Imperial Borderlands to Developing Nations. Indiana University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-253-30368-0.