Re-issued from earlier Mavi Boncuk posting with Soncino additions and new images.

A superb copy of the first book printed by the most famous of early early Hebrew printers, Gershom Soncino[1]. (Rare book and Special Collections Division, Jefferson Library, Library of Congress Photo) Gershon b. Moses Soncino (in Italian works, Jeronimo Girolima Soncino; in Latin works, Hieronymus Soncino): The most important member of the family; born probably at Soncino; died at Constantinople 1533.

Although Hebrew presses operated in Spain and Portugal during the 15th century, due to persecutions and expulsions many incunables printed there did not survive in more than one copy or in complete copies; of those that did, fragments are extremely rare or unique (and it is assumed that some Iberian Hebrew incunables have been lost altogether). Printing was introduced to the Ottoman Empire and North Africa by Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal, and in the subsequent centuries books in Hebrew and other languages were printed throughout the "Sephardic diaspora," in Turkey, Greece, North Africa, the Orient, Western Europe (Italy, Holland, Germany), and elsewhere. The geographic range of the Sephardic world is manifest in that a third of the surviving books in any exhibited collection of early Jewish printing are Sephardic works by Sephardic Jewish authors.

Mavi Boncuk |

(1500-42): This period is distinguished by the spread of Jewish presses to the Turkish and Holy Roman empires. In Constantinople, Hebrew printing was introduced by David Naḥmias and his son Samuel about 1503; and they were joined in the year 1530 by Gershon Soncino[1], whose work was taken up after his death by his son Eleazar. . Gershon Soncino put into type the first Karaite work printed (Bashyaẓi's "Adderet Eliyahu.") in 1531. In Salonica, Don Judah Gedaliah printed about 30 Hebrew works from 1500 onward, mainly Bibles, and Gershon Soncino, the Wandering Jew of early Hebrew typography, joined his kinsman Moses Soncino, who had already produced 3 works there (1526-27); Gershon printed the Aragon Maḥzor (1529) and Ḳimḥi's "Shorashim" (1533). The prints of both these Turkish cities were not of a very high order. The works selected, however, were important for their rarity and literary character. The type of Salonica imitates the Spanish Rashi type.

![]() Unlike other editions, the text in this polyglot Pentateuch is set entirely in Hebrew characters. While Diaspora Jews were generally fluent in the vernaculars of their host nations, they often chose to write those languages using the Hebrew alphabet, with which they were most adept. The original Hebrew text of the Pentateuch is at the center, flanked by the Judeo-Persian and Aramaic versions on the right and left, respectively. The Judeo-Arabic translation appears above, and the commentary of Rashi is below.

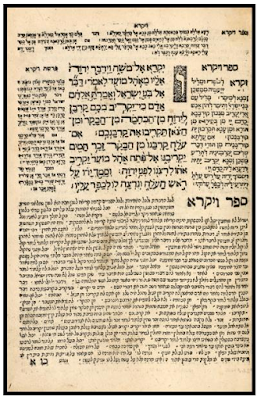

Unlike other editions, the text in this polyglot Pentateuch is set entirely in Hebrew characters. While Diaspora Jews were generally fluent in the vernaculars of their host nations, they often chose to write those languages using the Hebrew alphabet, with which they were most adept. The original Hebrew text of the Pentateuch is at the center, flanked by the Judeo-Persian and Aramaic versions on the right and left, respectively. The Judeo-Arabic translation appears above, and the commentary of Rashi is below.

Constantinople (Istanbul), as capital of the Ottoman Empire and a refuge for Jews expelled from Western Europe, supported a linguistically diverse Jewish community. Another polyglot edition was printed there the following year, with Judeo-Greek replacing the Judeo-Persian.

Library Catalog Record | Hamishah Humshei Torah [Pentateuch, with translations in Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, and the Commentary of Rashi]. Constantinople: Eliezer Soncino, AM 5306 (1546 CE). NYPL, Dorot Jewish Division.

The idea of representing the title-page of a book as a door with portals appears to have attracted Jewish as well as other printers. The fashion appears to have been started at Venice about 1521, whence it spread to Constantinople. Information is often given in these colophons as to the size of the office and the number of persons engaged therein and the character of their work. The master printer was occasionally assisted by a manager or factor ("miẓib 'al hadefus"). Besides these there was a compositor ("meẓaref" or "mesadder"), first mentioned in the "Leshon Limmudim" of Constantinople (1542). Many of these compositors were Christians, as in the workshop of Juan di Gara, or at Frankfort-on-the-Main, or sometimes even proselytes to Judaism

Toward the end of the sixteenth century Donna Reyna Mendesia founded what might be called a private printing-press at Belvedere or Kuru Chesme (1593). The next century the Franco family, probably from Venice, also established a printing-press there, and was followed by Joseph b. Jacob of Solowitz (near Lemberg), who established at Constantinople in 1717 a press which existed to the end of the century. He was followed by a Jewish printer from Venice, Isaac de Castro (1764-1845), who settled at Constantinople in 1806; his press is carried on by his son Elia de Castro, who is still the official printer of the Ottoman empire. Both the English and the Scotch missions to the Jews published Hebrew works at Constantinople.

Together with Constantinople should be mentioned Salonica, where Judah Gedaliah began printing in 1512, and was followed by Solomon Jabez (1516) and Abraham Bat-Sheba (1592). Hebrew printing was also conducted here by a convert, Abraham ha-Ger. In the eighteenth century the firms of Naḥman (1709-89), Miranda (1730), Falcon (1735), and Ḳala'i (1764) supplied the Orient with ritual and halakic works. But all these firms were outlived by an Amsterdam printer, Bezaleel ha-Levi, who settled at Salonica in 1741, and in whose name the publication of Hebrew and Ladino books and periodicals still continues. The Jabez family printed at Adrianople before establishing its press at Salonica; the Hebrew printing annals of this town had a lapse until 1888, when a literary society entitled Doreshe Haskalah published some Hebrew pamphlets, and the official printing-press of the vilayet printed some Hebrew books.

From Salonica printing passed to Safed in Palestine, where Abraham Ashkenazi established in 1588 a branch of his brother Eleazar's Salonica house. According to some, the Shulḥan 'Aruk was first printed there. In the nineteenth century a member of the Bak family printed at Safed (1831-41), and from 1864 to 1884 Israel Dob Beer also printed there. So too at Damascus one of the Bat-Shebas brought a press from Constantinople in 1706 and printed for a time. In Smyrna Hebrew printing began in 1660 with Abraham b. Jedidiah Gabbai; and no less than thirteen other establishments have from time to time been founded. One of them, that of Jonah Ashkenazi, lasted from 1731 to 1863. E. Griffith, the printer of the English Mission, and B. Tatiḳian, an Armenian, also printed Hebrew works at Smyrna. A single work was printed at Cairo in 1740. Hebrew printing has also been undertaken at Alexandria since 1875 by one Faraj Ḥayyim Mizraḥi.

Israel Bak, who had reestablished the Safed Hebrew press, and was probably connected with the Bak family of Prague, moved to Jerusalem in 1841 and printed there for nearly forty years, up to 1878.

One of the Jerusalem printers, Elijah Sassoon, moved his establishment to Aleppo in 1866. About the same time printing began in Bagdad under Mordecai & Co., who recently have had the competition of Judah Moses Joshua and Solomon Bekor Ḥussain. At Beirut the firm of Selim Mann started printing in 1902. Reverting to the countries formerly under Turkish rule, it may be mentioned that Hebrew and Ladino books have been printed at Belgrade since 1814 at the national printing establishment by members of the Alḳala'i family. Later Jewish printing-houses are those of Eleazar Rakowitz and Samuel Horowitz (1881). In Sarajevo Hebrew printing began in 1875; and another firm, that of Daniel Kashon, started in 1898. At Sofia there have been no less than four printing-presses since 1893, the last that of Joseph Pason (1901), probably from Constantinople. Also at Rustchuk, since 1894, members of the Alḳala'i family have printed, while at Philippopolis the Pardo Brothers started their press in 1898 before moving it to Safed. Altogether in the Levant about eighteen cities have had 121 Hebrew printing establishments between 1504 and 1905. Their productions have been mainly rituals, responsa of local rabbis, and Cabala; the type has been mostly Rashi, and the result has not been very artistic.

![]() [1] More than one-third of the one hundred and sixty or so Hebrew incunabula which have survived were products of the Soncino family. The Soncino family (Hebrew: משפחת שונצינו) was an Italian Ashkenazic Jewish family of printers, deriving its name from the town of Soncino in the duchy of Milan. It traces its descent through a Moses of Fürth, who is mentioned in 1455, back to a certain Moses of Speyer, of the middle of the 14th century. The first of the family engaged in printing was Israel Nathan b. Samuel, the father of Joshua Moses and the grandfather of Gershon. He set up his Hebrew printing-press in Soncino in the year 1483, and published his first work, the tractate Berakot, February 2, 1484. The press was moved about considerably during its existence. It can be traced at Soncino in 1483-86; Casal Maggiore, 1486; Soncino again, 1488–90; Naples, 1490–92; Brescia, 1491–1494; Barco, 1494–97; Fano, 1503-6; Pesaro, 1507–20 (with intervals at Fano, 1516, and Ortona, 1519); Rimini, 1521–26. Members of the family were at Constantinople between 1530 and 1533, and had a branch establishment at Salonica in 1532–33. Their printers' mark was a tower, probably connected in some way with Casal Maggiore. The last of the Soncinos was Eleazar b. Gershon, who worked at Constantinople from 1534 to 1547.

[1] More than one-third of the one hundred and sixty or so Hebrew incunabula which have survived were products of the Soncino family. The Soncino family (Hebrew: משפחת שונצינו) was an Italian Ashkenazic Jewish family of printers, deriving its name from the town of Soncino in the duchy of Milan. It traces its descent through a Moses of Fürth, who is mentioned in 1455, back to a certain Moses of Speyer, of the middle of the 14th century. The first of the family engaged in printing was Israel Nathan b. Samuel, the father of Joshua Moses and the grandfather of Gershon. He set up his Hebrew printing-press in Soncino in the year 1483, and published his first work, the tractate Berakot, February 2, 1484. The press was moved about considerably during its existence. It can be traced at Soncino in 1483-86; Casal Maggiore, 1486; Soncino again, 1488–90; Naples, 1490–92; Brescia, 1491–1494; Barco, 1494–97; Fano, 1503-6; Pesaro, 1507–20 (with intervals at Fano, 1516, and Ortona, 1519); Rimini, 1521–26. Members of the family were at Constantinople between 1530 and 1533, and had a branch establishment at Salonica in 1532–33. Their printers' mark was a tower, probably connected in some way with Casal Maggiore. The last of the Soncinos was Eleazar b. Gershon, who worked at Constantinople from 1534 to 1547.

It is obvious that the mere transfer of their workshop must have had a good deal to do with the development of the printing art among the Jews, both in Italy and in Turkey. While they devoted their main attention to Hebrew books, they published also a considerable number of works in general literature, and even religious works with Christian symbols. The Soncino prints, though not the earliest, excelled all the others in their perfection of type and their correctness.

The Soncino house is distinguished also by the fact that the first Hebrew Bible was printed there. An allusion to the forthcoming publication of this edition was made by the type-setter of the "Sefer ha-Ikkarim" (1485), who, on page 45, parodied Isa. ii. 3 thus: "Out of Zion shall go forth the Law, and the word of the Lord from Soncino" (). Abraham b. Hayyim's name appears in the Bible edition as type-setter, and the correctors included Solomon b. Perez Bonfoi ("Mibhar ha-Peninim"), Gabriel Strassburg (Berakot), David b. Elijah Levi and Mordecai b. Reuben Baselea (Hullin), and Eliezer b. Samuel ("Yad").

Eleazar b. Gershon Soncino: Printer between 1534 and 1547. He completed "Miklol" (finished in 1534), the publication of which had been begun by his father, and published "Meleket ha-Mispar," in 1547; and Isaac b. Sheshet's responsa, likewise in 1547.

Moses Soncino: Printer at Salonica in 1526 and 1527; assisted in the printing of the Catalonian Mahzor and of the first part of the Yalkut.

A superb copy of the first book printed by the most famous of early early Hebrew printers, Gershom Soncino[1]. (Rare book and Special Collections Division, Jefferson Library, Library of Congress Photo) Gershon b. Moses Soncino (in Italian works, Jeronimo Girolima Soncino; in Latin works, Hieronymus Soncino): The most important member of the family; born probably at Soncino; died at Constantinople 1533.

Although Hebrew presses operated in Spain and Portugal during the 15th century, due to persecutions and expulsions many incunables printed there did not survive in more than one copy or in complete copies; of those that did, fragments are extremely rare or unique (and it is assumed that some Iberian Hebrew incunables have been lost altogether). Printing was introduced to the Ottoman Empire and North Africa by Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal, and in the subsequent centuries books in Hebrew and other languages were printed throughout the "Sephardic diaspora," in Turkey, Greece, North Africa, the Orient, Western Europe (Italy, Holland, Germany), and elsewhere. The geographic range of the Sephardic world is manifest in that a third of the surviving books in any exhibited collection of early Jewish printing are Sephardic works by Sephardic Jewish authors.

Mavi Boncuk |

(1500-42): This period is distinguished by the spread of Jewish presses to the Turkish and Holy Roman empires. In Constantinople, Hebrew printing was introduced by David Naḥmias and his son Samuel about 1503; and they were joined in the year 1530 by Gershon Soncino[1], whose work was taken up after his death by his son Eleazar. . Gershon Soncino put into type the first Karaite work printed (Bashyaẓi's "Adderet Eliyahu.") in 1531. In Salonica, Don Judah Gedaliah printed about 30 Hebrew works from 1500 onward, mainly Bibles, and Gershon Soncino, the Wandering Jew of early Hebrew typography, joined his kinsman Moses Soncino, who had already produced 3 works there (1526-27); Gershon printed the Aragon Maḥzor (1529) and Ḳimḥi's "Shorashim" (1533). The prints of both these Turkish cities were not of a very high order. The works selected, however, were important for their rarity and literary character. The type of Salonica imitates the Spanish Rashi type.

Unlike other editions, the text in this polyglot Pentateuch is set entirely in Hebrew characters. While Diaspora Jews were generally fluent in the vernaculars of their host nations, they often chose to write those languages using the Hebrew alphabet, with which they were most adept. The original Hebrew text of the Pentateuch is at the center, flanked by the Judeo-Persian and Aramaic versions on the right and left, respectively. The Judeo-Arabic translation appears above, and the commentary of Rashi is below.

Unlike other editions, the text in this polyglot Pentateuch is set entirely in Hebrew characters. While Diaspora Jews were generally fluent in the vernaculars of their host nations, they often chose to write those languages using the Hebrew alphabet, with which they were most adept. The original Hebrew text of the Pentateuch is at the center, flanked by the Judeo-Persian and Aramaic versions on the right and left, respectively. The Judeo-Arabic translation appears above, and the commentary of Rashi is below.Constantinople (Istanbul), as capital of the Ottoman Empire and a refuge for Jews expelled from Western Europe, supported a linguistically diverse Jewish community. Another polyglot edition was printed there the following year, with Judeo-Greek replacing the Judeo-Persian.

Library Catalog Record | Hamishah Humshei Torah [Pentateuch, with translations in Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic, Judeo-Persian, and the Commentary of Rashi]. Constantinople: Eliezer Soncino, AM 5306 (1546 CE). NYPL, Dorot Jewish Division.

The idea of representing the title-page of a book as a door with portals appears to have attracted Jewish as well as other printers. The fashion appears to have been started at Venice about 1521, whence it spread to Constantinople. Information is often given in these colophons as to the size of the office and the number of persons engaged therein and the character of their work. The master printer was occasionally assisted by a manager or factor ("miẓib 'al hadefus"). Besides these there was a compositor ("meẓaref" or "mesadder"), first mentioned in the "Leshon Limmudim" of Constantinople (1542). Many of these compositors were Christians, as in the workshop of Juan di Gara, or at Frankfort-on-the-Main, or sometimes even proselytes to Judaism

Toward the end of the sixteenth century Donna Reyna Mendesia founded what might be called a private printing-press at Belvedere or Kuru Chesme (1593). The next century the Franco family, probably from Venice, also established a printing-press there, and was followed by Joseph b. Jacob of Solowitz (near Lemberg), who established at Constantinople in 1717 a press which existed to the end of the century. He was followed by a Jewish printer from Venice, Isaac de Castro (1764-1845), who settled at Constantinople in 1806; his press is carried on by his son Elia de Castro, who is still the official printer of the Ottoman empire. Both the English and the Scotch missions to the Jews published Hebrew works at Constantinople.

Together with Constantinople should be mentioned Salonica, where Judah Gedaliah began printing in 1512, and was followed by Solomon Jabez (1516) and Abraham Bat-Sheba (1592). Hebrew printing was also conducted here by a convert, Abraham ha-Ger. In the eighteenth century the firms of Naḥman (1709-89), Miranda (1730), Falcon (1735), and Ḳala'i (1764) supplied the Orient with ritual and halakic works. But all these firms were outlived by an Amsterdam printer, Bezaleel ha-Levi, who settled at Salonica in 1741, and in whose name the publication of Hebrew and Ladino books and periodicals still continues. The Jabez family printed at Adrianople before establishing its press at Salonica; the Hebrew printing annals of this town had a lapse until 1888, when a literary society entitled Doreshe Haskalah published some Hebrew pamphlets, and the official printing-press of the vilayet printed some Hebrew books.

From Salonica printing passed to Safed in Palestine, where Abraham Ashkenazi established in 1588 a branch of his brother Eleazar's Salonica house. According to some, the Shulḥan 'Aruk was first printed there. In the nineteenth century a member of the Bak family printed at Safed (1831-41), and from 1864 to 1884 Israel Dob Beer also printed there. So too at Damascus one of the Bat-Shebas brought a press from Constantinople in 1706 and printed for a time. In Smyrna Hebrew printing began in 1660 with Abraham b. Jedidiah Gabbai; and no less than thirteen other establishments have from time to time been founded. One of them, that of Jonah Ashkenazi, lasted from 1731 to 1863. E. Griffith, the printer of the English Mission, and B. Tatiḳian, an Armenian, also printed Hebrew works at Smyrna. A single work was printed at Cairo in 1740. Hebrew printing has also been undertaken at Alexandria since 1875 by one Faraj Ḥayyim Mizraḥi.

Israel Bak, who had reestablished the Safed Hebrew press, and was probably connected with the Bak family of Prague, moved to Jerusalem in 1841 and printed there for nearly forty years, up to 1878.

One of the Jerusalem printers, Elijah Sassoon, moved his establishment to Aleppo in 1866. About the same time printing began in Bagdad under Mordecai & Co., who recently have had the competition of Judah Moses Joshua and Solomon Bekor Ḥussain. At Beirut the firm of Selim Mann started printing in 1902. Reverting to the countries formerly under Turkish rule, it may be mentioned that Hebrew and Ladino books have been printed at Belgrade since 1814 at the national printing establishment by members of the Alḳala'i family. Later Jewish printing-houses are those of Eleazar Rakowitz and Samuel Horowitz (1881). In Sarajevo Hebrew printing began in 1875; and another firm, that of Daniel Kashon, started in 1898. At Sofia there have been no less than four printing-presses since 1893, the last that of Joseph Pason (1901), probably from Constantinople. Also at Rustchuk, since 1894, members of the Alḳala'i family have printed, while at Philippopolis the Pardo Brothers started their press in 1898 before moving it to Safed. Altogether in the Levant about eighteen cities have had 121 Hebrew printing establishments between 1504 and 1905. Their productions have been mainly rituals, responsa of local rabbis, and Cabala; the type has been mostly Rashi, and the result has not been very artistic.

It is obvious that the mere transfer of their workshop must have had a good deal to do with the development of the printing art among the Jews, both in Italy and in Turkey. While they devoted their main attention to Hebrew books, they published also a considerable number of works in general literature, and even religious works with Christian symbols. The Soncino prints, though not the earliest, excelled all the others in their perfection of type and their correctness.

The Soncino house is distinguished also by the fact that the first Hebrew Bible was printed there. An allusion to the forthcoming publication of this edition was made by the type-setter of the "Sefer ha-Ikkarim" (1485), who, on page 45, parodied Isa. ii. 3 thus: "Out of Zion shall go forth the Law, and the word of the Lord from Soncino" (). Abraham b. Hayyim's name appears in the Bible edition as type-setter, and the correctors included Solomon b. Perez Bonfoi ("Mibhar ha-Peninim"), Gabriel Strassburg (Berakot), David b. Elijah Levi and Mordecai b. Reuben Baselea (Hullin), and Eliezer b. Samuel ("Yad").

Eleazar b. Gershon Soncino: Printer between 1534 and 1547. He completed "Miklol" (finished in 1534), the publication of which had been begun by his father, and published "Meleket ha-Mispar," in 1547; and Isaac b. Sheshet's responsa, likewise in 1547.

Moses Soncino: Printer at Salonica in 1526 and 1527; assisted in the printing of the Catalonian Mahzor and of the first part of the Yalkut.